The 3 Secrets To A Pure Carve

After all the time we spent on groomers last year (because the woods, without snowmaking, were frankly a bit scary), I have felt a re-awakening of the carved turn.

Have you felt it?

The ski industry over the past few seasons has been so focused on making skis true all-mountain masters, that the ability to hold and rip on a firm surface has taken a backseat to floating in the snow and releasing the turn.

Fifteen years ago when we lived through the side cut revolution, skis were evolving to allow mere mortals to feel a pure carved turn without having to go mach schnell. Back then everyone was obsessed with carving turns. Recreational ski equipment tried to emulate what the world’s best racers were doing. At the very least, it helped weekend warriors make some clean turns on their local hill.

Today, all the cool kids are talking about rocker, alpine touring skis and boots with a walk mode. Most recreational skis are no longer toned-down versions of race gear.

But that shouldn’t keep all of us from laying down trenches on our favorite trails, particularly in the early season before the woods build up a base.

While the term “carving” is known by most skiers, it is surprising how few skiers actually know how to carve a turn. SKI Magazine recently polled ski instructors from around the country and the consensus was that about 10 percent of skiers on a given hill can actually carve a turn, but many more think they are carving.

As a boot fitter, this reminds me of the statistic that 86 percent of skiers are in a boot at least one size too big. Is there a correlation? Yes!

There is a certain amount of accuracy needed to carve a turn well, and many skiers just aren’t set up for success. A proper fitting boot, with decent alignment of the foot, ankle, and knee goes a long way towards engaging the performance of a ski. Having a ski that is properly tuned with sharp edges, including more than the “standard” 2 degree side bevel, is also a step in the right direction.

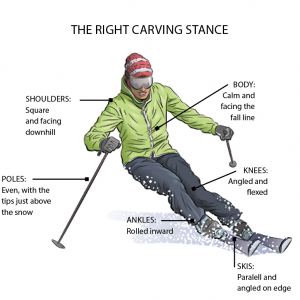

So, if you have proper fitting boots, tuned skis, and are standing on a well-groomed trail, what’s keeping the carve from happening? The three most common carving issues I see on the hill are the skier’s stance, a move I call the “push,” and basically just too much body English.

Find Your Stance

Many skiers don’t come down the hill in a functional or athletic stance. Having your feet a hip-width distance apart and holding a healthy amount of ankle flex into the front of your boots goes a long way to improving your ability to carve. You should ski in a stance that would give you a fighting chance of not falling over if your buddy came up and pushed you on the shoulder.

While standing on the flats, do a few hops off the ground where both skis leave the snow and stay level or horizontal. This will engage your ankle, and will usually help your feet find that functional hip width distance apart.

If you find it hard to either leave the ground, or to keep the skis horizontal when you do, this can be a sign of not being properly balanced in your boots. While leaving the ground is not a requirement of carving turns, being properly balanced in your boots is. A well-balanced stance gives you the chance to access and precisely control the edge angle of your skis and using your edges is essential to a well carved turn.

Roll Your Skis

Once you have a strong and efficient stance, you can move your body over this stable base of support. Far too many skiers push their feet away from where they want to go. If a skier is in a strong stance, with properly aligned boots, then he or she can move in the direction of travel which will engage the edges of the skis, and create a clean, carved turn. This is very different from pushing your feet and skis off to the right, to then try to make your body go to the left.

The next time you are in your gear, stand on a flat, or across the hill so you aren’t moving, and get in a good, athletic and balanced stance. From here, practice just rolling your skis up on edge using your feet and ankles to do so. Roll up into the edges of your skis slowly and smoothly while keeping both skis symmetrical and at the same edge angle. Also, be sure to practice making that progressive edging move in each direction (turn around to try the other side if you are on a slope, so you are always rolling the legs up the hill).

After you have a good feel for making this edging move statically, it is time to find a mellow slope that you can basically straight-line without fear of going too fast. Start straight down the hill in a strong and balanced stance, and then slowly roll your feet and ankles to put your skis on their edges. Don’t try to twist or turn the ski, just get a feel for what the shape of the skis does for you.

As soon as the skis start to change direction, roll back to the other side and engage the other set of edges. This will create a very shallow turn, and you will be going full speed. A carved turn like this will not slow you down.

This is the way racers ski a race course, and keep all of their speed while making turns around the gates. The challenge they face is in getting their skis to bend and make a carved turn tight enough to stay in the course and to make all the turns with very little skidding which slows them down.

This speed and efficiency is the fun of carving. It is also why it is so rarely seen on the slopes. If you were to ask a group of recreational skiers why they turn, all most all of them would say ‘to slow down.’ This view of turning connects the turning movement with braking for most skiers. Carving is different; carving is changing direction without braking, or losing speed.

Calm Your Body

So, how does this slow pure carving on a mellow slope become high speed performance carving? This move of just tilting your feet and ankles so that the skis engage the edges and carve is just the start. As the pitch of the hill increases, and speed increases, we need to continue to move our bodies farther into the turn and continue to increase the angle on our skis.

What starts with our feet and ankles becomes our knees, thighs and hips moving farther into each turn. While our lower body continues to move in and add more edge angle, this is complimented by our upper body staying level to the hill and not tipping over. This calmness and stability is something many skiers lack. If the shoulders and arms are leaning like an airplane wing making a turn, then the skis lose their ability to engage a high edge angle and continue to carve.

One of my favorite ways to calm my body and make sure I am staying level with my shoulders, so that my feet and legs can carve, is to do a pole dragging drill.

Make a run on a groomer and keep both of your poles close to vertical and sticking into the snow about a foot out to the side of your toes.

As you make a turn to, say the left, make sure both poles stay touching the ground. You will find that the tendency is to leave the left pole on the ground, but let the right one float off the snow. Drive down that outside shoulder and arm so that the pole stays in contact with the snow, and the legs can keep the skis on a higher edge. Your carve will be much stronger, and more balanced with this drill, because with level shoulders you will stay more balanced over the outside ski, and the movement of your upper body towards the outside of the turn will help your legs move farther inside of the turn. Keeping the arms and shoulders from tipping and twisting will really clean up your ability to carve your skis.

While carving isn’t everything, and most of our turns will have a bit of skid in them, the ability to purely carve a turn is mandatory for any expert skier. All we really do with our skis is tip them and turn them. All of our skiing is a mix of these skills of tipping and turning. The blend of these two movements is what determines the outcome of our turn.

In order to master the blending of the two skills and to ski all types of turns like an expert, we need to be able to seperate, and master these skills individually. A pure sideslip in one direction, connected to a pure sideslip in the other direction would be the application of turning without edging. Tipping the skis on their edge and letting the shape of the bent skis make the turn without any twisting or turning is the basis of carving. Any expert skier should be able to make this move.

The next time you find a nice newly-groomed piece of real estate, take the time to play with some of these ideas, and paint some railroad tracks all over that slope!

An examiner for the Eastern division of the Professional Ski Instructors of America (PSIA), Doug Stewart has been teaching skiing at Stowe for over 20 years. Stewart divides his winters between being a full time boot fitter at Skirack in Burlington, training the ski school staff and his clients at Stowe, and running certification training and exams. When he’s not at work, Stewart loves skiing with his wife, and chasing their 8- and 10-year-old sons around the slopes of Vermont.