Revenge of the Redneck Racers

Meet Vermont’s scrappiest, funniest, winningest World Cup caliber racers: The Redneck Racers from Cochran’s. All of the Redneck Racers have turned up at big races, and as of January, 2017, Robby Kelley scored his first World Cup points, finishing as the top American in the classic Wengen slalom.

In the spring of 2015, three members of Vermont’s famous Cochran ski racing family were invited to join the U.S. Ski Team for the 2015-16 season. Tim Kelley, son of one-time national champion Lindy Cochran Kelley, said yes, joining his cousin Ryan Cochran-Siegle on the squad. But in a move that surprised many, Tim’s younger brother, Robby, declined. Not because he didn’t want to compete on the international circuit, but because he wanted to do it on his own.

Not since Bode Miller formed his own “Team America” in 2007 has any American athlete competed successfully at the international level without the help and support of the U.S. Ski Team. But for the past season, both Tim and Robby Kelley—along with fellow Vermonters Andrew McNealus and Tucker Marshall—have traveled the international circuit as the homespun, self-funded, Vermont-proud “Redneck Racing” team. Scrappy and hard-working, the Rednecks turned up at the biggest ski races in Europe and North America, bringing with them more than a touch of underdog defiance and a healthy dose of fun.

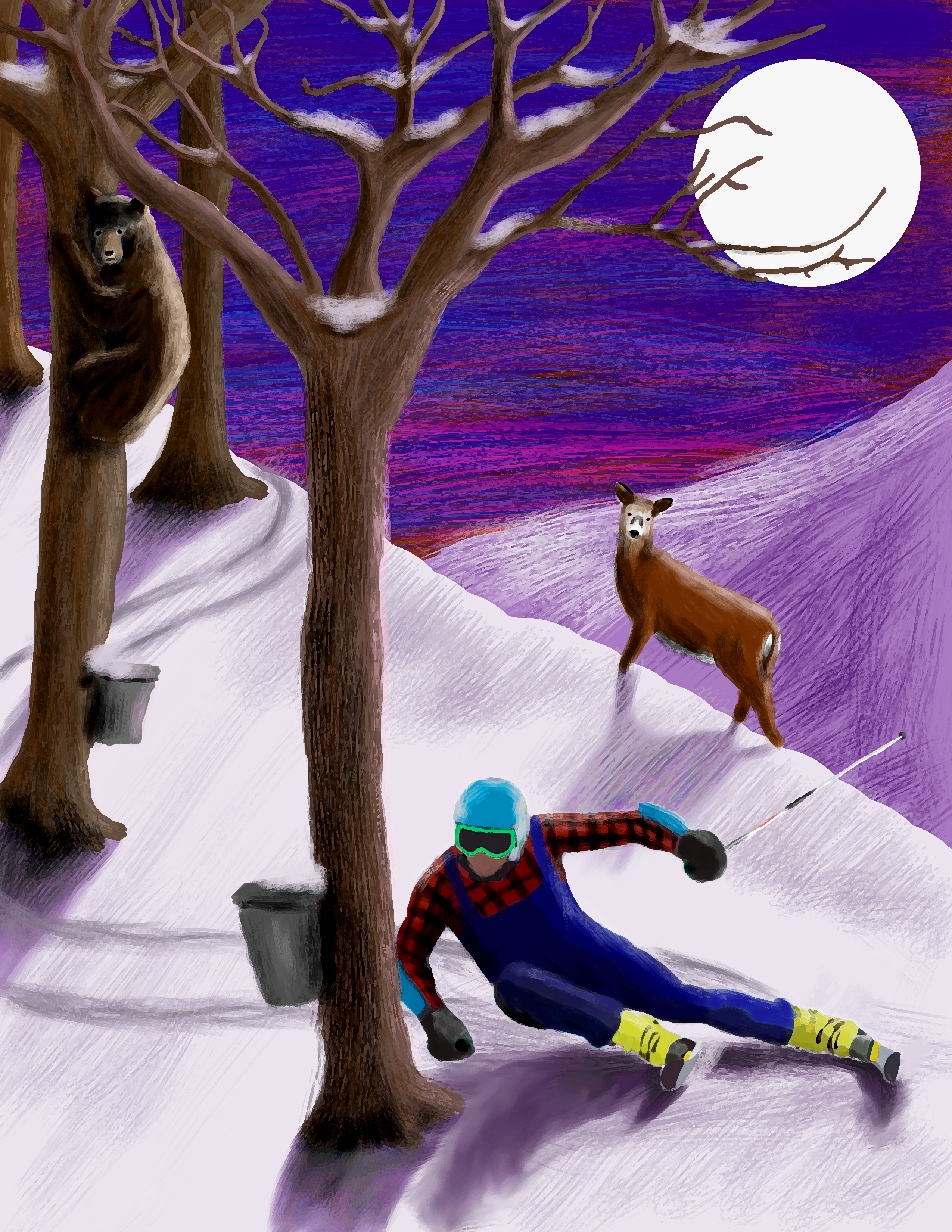

They competed against members of national teams that traveled with an entourage of coaches, team vehicles, ski technicians and trainers. Instead of sporting the U.S. Ski Team suits, the Redneck Racing team had sponsor Podiumwear make them speed suits designed to look like flannel shirts and denim overalls or hunter’s camouflage. Instead of staying at luxury digs, the Vermonters crammed into a single hotel room, sharing beds, and sometimes found floor space, in other racers’ rooms. “We’d always rent the cheapest cars we could,” Robby recalls. “So last year at the Kranjska Gora (Slovenia) World Cup I was driving around a little convertible in the winter because that was the cheapest car they had. I felt pretty cool rolling up to the race with the top down.” Instead of having specialized training programs and fancy gyms, they rode bikes. To test his sprints, Robby will play a game of throwing a football, and then race forward to catch it himself. (The caption for a video of this on the Redneck Racing Facebook page reads “Robby playing football with his friends.”) For training, the Rednecks raced and coached each other at the tiny Cochran ski hill in Richmond and at the Mt. Mansfield Ski Club in Stowe. For energy, they downed packets of the Slopeside Syrup the family produces from a sugarbush just off the slopes where Robby and Tim grew up skiing.

To pay for their race entries and travel, the Rednecks raised money every which way they could: They launched an online fundraising campaign and they signed on equipment and other sponsors. Robby, who studied art and graphic design, made T-shirts, one of which featured a skiing bear. They sold like hotcakes.

Ski Racing’s Unlikely Royalty

Though they grew up skiing on a tiny Vermont ski hill with just 350 feet of vertical and three surface lifts, Robby and Tim Kelley come from one of the strongest racing lineages in the United States, and perhaps the world. Their mom is the former Olympic ski racer and national champion Lindy Cochran Kelley. Her two sisters—Barbara Ann and Marilyn—and her brother, Bob, were all Olympic skiers and champions in their own right. All three of Lindy’s children (Tim, Jessica and Robby) have made the U.S. Ski Team at least once. In all, 10 Cochran family members (see “The Cochran Dynasty” on the following page), spanning two generations, have competed for the U.S. Ski Team.

As a junior skier, though, Robby failed to make the U.S. Ski Team so he enrolled at the University of Vermont (UVM) where his brother Tim was also in school. There, his results on the college circuit earned Robby another look from the U.S team coaches. They offered him a national team spot for the 2011-12 season. Robby didn’t disappoint: he won both the U.S. National and North American Cup titles in giant slalom. That was followed in 2012-13 with top World Cup finishes, 26th in the giant slalom in Schladming, Austria, and 28th in the famed Adelboden giant slalom in Switzerland. Robby was on an upward roll and enjoying every minute. Then came setbacks. Robby wasn’t selected for the 2014 Sochi Olympic squad and, subsequently, was cut from the national team altogether. By that time, Tim had lost his U.S. Ski Team spot but was winning for UVM—he was NCAA slalom champion in 2011—and winning FIS races (the elite international-level races).

By 2014, both brothers were off the team but skiing well and injury-free, and looking to return to the highest world stage: the World Cup circuit. “I definitely feel like I have another level or more,” Robby said at the time. Tim and Robby were already traveling together off and on, sharing expenses and experiences and often teaming up to train with their Vermont buddies, Andrew McNealus and Tucker Marshall. Working together more officially was a logical next step. “We’re all from Vermont,” Robby said, “and we’re all trying to make it to the top.” The Redneck Racing Team was hatched in the spring of 2014. For both Kelleys, the 2014-15 Redneck season was a success.

Tim, at 29 the elder statesmen of the current crop of Cochran progeny, notched two North American Cup slalom wins and finished in the top ten in three others. The NorAms, or “continental cups,” are qualifiers for the World Cup. Tim’s finishes earned him a spot in the biggest show of the season, the World Championships at Vail, last February. There, he stormed into 23rd in the slalom, the second fastest American in the race, just two positions behind Ted Ligety. He finished out the season with a third in the national championships in Maine. Those results secured Tim a starting position in this season’s World Cup races and got him back on the national team. For his part, Robby won six major FIS races and was top five in nine others, including three NorAms.

But even though Robby’s 2014-15 results were excellent, they failed by a thin margin to qualify him for the team. The U.S. Ski Team coaching staff wanted Robby anyway. “Though he didn’t make the criteria for the B or the C team, Robby was nominated to the C team on coaches’ discretion,” head men’s coach Sasha Rearick said this fall. “Robby and (U.S. men’s Europa Cup team coach) Ian Lochhead wanted to work together. Ian really wanted Robby in the group; he has a lot of respect for him.” The admiration was mutual. Still, Robby said “no.” “It was really difficult,” Robby said solemnly in a recent interview. “I really like Ian and I have a lot of friends on the team.” He paused, then added: “But I wanted my own program where I can focus solely on myself.”

Making it as a Redneck

“What’s a Redneck?” the website www.redneck-racing.com asks, and then answers: “Anyone who defies the odds of society and is lacking a general compliance with those who say you are done.” When Bode Miller went off on his own to form “Team America” in 2007, it was an acrimonious split with the U.S. Team, something that had been brewing for several years. His defection, his second “American” team on the World Cup, and his poaching of U.S. coaches, deeply irked U.S. Ski Association executives. Even harder for them to take was that Miller would go on to win the overall World Cup in 2008. But that was followed by an unsuccessful injury-plagued season and he subsequently returned to the U.S. team. This October, Miller, 38, announced he would not be racing.

Robby and Bode have some similarities: the two racers are both exceptionally talented skiers, and unconventional, creative people—“strong-minded,” is how Rearick described Robby recently. But Robby’s decision to turn down the national team came with no acrimony, and his case is clearly different. Bode left a fully funded slot on the A team where he was a star with wide name recognition and top-ten world rankings; Robby is ranked 52nd in the world and 6th in the United States in slalom and his C team offer came with a price tag. While the U.S. Ski Team helps defray the more than $100,000 it costs for a team member’s training, travel and coaching (among other things), those who are on the B, C and D teams have to fork up at least $20,000 of that from their own pockets.

For Robby, that was just too steep.

Robby’s choice raises perennial questions about U.S. funding for team athletes and whether the sport’s governing body, the United States Ski and Snowboard Association, has structured the best program to produce world champions. When I reached out to the U.S. Ski Team about Robby’s decision, both Rearick and USSA CEO Tiger Shaw got on the phone. “We wish Robby had accepted, obviously,” said Shaw, himself a former Olympian whose extended family still owns Shaw’s General Store in Stowe. “He’s a great guy and a terrific athlete. The coaches wanted him.” Rearick said his coaching staff encouraged Robby to consider the obvious upsides of joining the U.S. team—the coaching, the logistical support, the training facilities, the equipment technicians and more.

Even with the pay-to-join fee, most athletes would never think of turning down an offer from the U.S. team; it’s every ski racer’s singular objective. And, if it comes with a bill, well, you scratch together the money from family, sponsors and friends and you do it. When decision time came, Robby conferred with coaches, mentors, family and friends. He knew the pros of being with the team. He added up the cons of going it alone. In addition to the coaching, off-slope training, physical therapy, ski and equipment preparation and behind-the-scenes support, he’d miss intangible psychic and emotional benefits of working shoulder to shoulder with the best skiers in America.

With Tim and cousin Ryan Cochran-Siegle moving onto the U.S. squad, the choice to go it alone was even more difficult. “It made sense for them. Ryan is coming off an injury and Tim has World Cup starts all season,” Robby said. For Robby, it came down to money and the desire to design his own season and train independently and with the two remaining Rednecks. “I’m going to be getting more runs in, I’m going to be able to listen and respond to my own body,” he said. He would be able to rest and heal when he needed to, without worrying he might lose standing with the coaching staff. “I will be able to have total control over my race and training program, and I will be able to focus on slalom,” rather than following the national team’s training and racing script.

Robby’s O.P.

When asked about Robby’s decision, his long-time friend and Mt. Mansfield Ski Club coach Scott Moriarty replied: “Expected. Robby is and always has been O.P. (on his ‘own program’). He’s always been committed to his own ideas and he has always followed through on his own ideas.” Since he was a teenager, Robby has had a reserved, soft-spoken manner about him, Moriarty says. And an inner intensity: He took all his sports very seriously. He’d fight for the wins, and take losses hard. “Robby and Timmy are kids with roots who are humble and engaging,” said Lori Furrer, the director of the Mt. Mansfield Winter Academy where both Kelleys were students. “They never made a fuss or complained about how hard anything was—they put their heads down and got it done.”

Robby set a goal of raising a little less than $20,000 to cover all his expenses for the 2015-16 season. He trained with Mt. Mansfield Ski Club (MMSC) and at Cochran’s—perhaps getting occasional coaching from his aunt, Olympic gold medalist Barbara Ann Cochran, and the mind-boggling web of other champion family members, such as cousin Jimmy Cochran. The independent thing worked. “I’m able to work with different groups and I had a lot of help throughout the summer and fall,” Robby reported in late October 2015. “I had two weeks in France with the Mt. Mansfield Ski Club, a month in Australia with Mt. Hotham Racing Squad and am currently in Pitzal, Austria with Race Center Benni Raich, which was set up by Aldo Radamus.” (Radamus, the director of Ski and Snowboard Club Vail, is Redneck Andrew McNealus’s uncle. Thanks to that connection they not only lined up training in Austria, but in Vail as well.) “So I’ve had a ton of help to make this possible. But I don’t have any coach of my own.”

Having a top athlete decide to go it alone got Tiger Shaw’s attention, as the question of athlete funding is a chief concern. Shaw said he can justify charging U.S. Ski Team members but he’d rather not have to. “What people don’t understand is the overall financial picture, the cost of creating the infrastructure of what makes a team. We are actively working on a new campaign to bridge the funding gap,” Shaw said, in the hopes that in the future athletes like Robby may not have to cover so much of the cost—or any of it. The decision to charge some athletes is a matter of trying to include as many as possible on the team, Shaw explained. The teams now comprise a record 200 athletes, combined. The prevailing wisdom is that maximizing that number—exposing more athletes to top training and competition—increases America’s chances of producing champions.

The alternative would be to cut team ranks and extend funding to every member, or to raise more money, which is what Shaw is doing. The other question Shaw and USSA higher-ups hear constantly: Why does the USSA charge while most of the top European teams don’t? As a rule, top European teams spend more per athlete than the Americans and don’t require athletes to share in the costs, Shaw concedes. That has a lot to do with the fact that in Europe, to varying degrees, ski teams get government funding. The Americans get none. The USSA raises all its funds from corporate and private sponsors and donors, and derives income from an endowment. Out of the USSA’s operating budget of about $32 million, $20.8 million is spent on athletes. The money is used for everything from running competitions to building and sustaining the teams (snowboard, Nordic and alpine), Shaw says. The Indy Racer Individualism like Robby’s is key to ski racing success, and a good coach strikes the right balance between the needs and objectives of the individual and those of the team, Rearick said.

Many of the stars on the tour, including Americans Lindsey Vonn, Mikaela Shiffrin, Ted Ligety and Julia Mancuso, have earned the space to operate more independently while remaining key members of the team. Some get their own coaching and training regimens, among other things. They can pick and choose their rest days and races without fear of slipping in the coaches’ eyes. The successes that result from that independence are why Robby Kelley’s choice resonates. But Rearick is emphatic: skiers need the right coaching to reach their peaks. “The coach’s role,” he said pointedly, “is to guide athletes to places they can’t get to alone.

Robby, however, is reaching peaks on his own. In the summer of 2015 he competed in the Australian national championships (foreigners can enter national championships anywhere) and won. Tim was sixth. Ten days later Robby scored the best slalom finish of his life, winning an Australian/New Zealand Cup race ahead of a handful of guys who regularly score well on the World Cu. Robby’s objective for that season, which began in late October 2015, was to compete in races that are automatic qualifiers for the World Cup. It’s pretty much what he would be doing as a member of the national team.

Instead, he’ll be the Redneck Vermonter in the race. And proud of it. Watch vtskiandride.com for more updates and video footage of the Redneck Racers.

Since the 2015-2016 season, Robby’s dedication to Redneck Racing has paid off.

Pingback: Vermont Sports Magazine | Your Guide to the Outdoors in Northern New England