And the Forecast Calls For..

This fall we talked to top meteorologists about what this winter would hold. Here’s what we heard. For their specific predictions about when it will snow, where and how much, see 4 Forecasters, 7 Predictions

Last winter we prayed to Ullr, did snow dances, put spoons under our pillows, and wore our pajamas inside out—only to have a season of record warm temperatures and scant snowfall.

We emerged this spring disappointed, and perhaps bewildered—but compared to the ski resorts and the local economy, we were relatively unscathed.

Win Smith, the owner of Sugarbush Resort and an avid skier, felt our pain—doubly. Last season marked the second to lowest snowfall in the resort’s history, and with a total of only 156 inches (compared with 250 in an average year), Sugarbush saw a 15 percent decline in revenue. Smith estimates the industry lost about $140 million. “It was a tough year,” Smith said. “We had good reserves, so we were able to get through this winter okay, but two or three of them would be rough.” Despite Mother’s Nature’s refusal to cooperate, thanks to snowguns Sugarbush skiers were still bashing bumps on closing day, May 1.

If we’re going to point fingers, there were two culprits to blame for last season’s dismal conditions. The first is climate change—last year was one of the top five hottest years for our planet since the turn of the century, and it’s no big surprise that 2016 is on track to be the hottest on record.

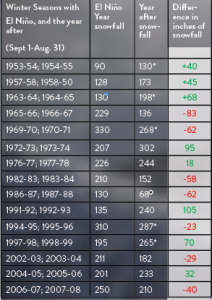

The second and perhaps more influential culprit was El Niño, the warm current that pushes north along the Pacific coast every few years. Last year’s El Niño tied with the winter of ‘97-‘98 for the strongest on record.

“The big story with last winter was not just the fact that there was an El Niño, but the fact that there was such a strong El Niño,” says Josh Fox, a meteorologist and author of Mad River Glen’s Single Chair Weather Blog. “On the blog, I kind of coined the term ‘super Niño.’ There have been about 60 to 70 years of recorded data in the equatorial Pacific where they measure the strength of an El Niño or La Niña. There are only four in the last 70 years that are in the same league as what we saw last winter.”

Defined most simply, El Niño occurs when surface temperatures in the eastern Pacific Ocean rise 1.5 degrees Celsius or more above the ocean’s average temperature and persist for several months.

As temperatures rise above the norm, El Niño grows stronger. Over last winter, temperatures rose 2.3 degrees Celsius above the eastern Pacific average, higher than almost ever before.

During a normal year, the trade winds push warm surface waters toward Asia, sending the deep cold water near South America upwards. Picture a bath in which cooler water rests on the bottom of the tub: if you push the higher, warmer water away, cold water rises to the top, filling the gap.

But during El Niño, the trade winds weaken. Warm water isn’t pushed west, cold water isn’t pushed up and a chain of consequences ensues. Temperatures climb off the coast of California. The southern United States typically becomes wetter, and the Northwest drier. Warm air comes streaming in from the west, carried on the back of a jet stream that has intensified while brewing in the Pacific.

The jet stream also shifts south and brings stormy weather with it. El Niño doesn’t always tamper with snowfall (and it doesn’t hit the East Coast the same way every time) but it’s known to bring mild and warmer-than-average weather to the Northeast. This year, it brought a relentless westerly flow of warmer air that kept us from settling into our mittens and ski boots.

The remarkable strength of the 2016 El Niño–defined by that record high 2.3 degrees Celsius rise in Pacific temperatures—bolstered its epic manifestation in North America.

And New England was hit hard.

In terms of skiing, Vermont had one of its worst years in history. The Green Mountain State saw a 30 percent decrease in visitors with only 3.2 million skiers compared to 4.67 million the year before, causing us to fall behind Colorado, California and Utah.

That’s right, sea surface temperatures in the eastern Pacific took a nosedive in June, and the overall global temperature fell by 0.37 degrees Celsius—the second fastest that recorded global temperature has ever fallen.

If sea surface temperatures continue to drop, we’ll be headed for El Niño’s sister, La Niña. While warm water in the eastern Pacific designates an El Niño, cooler-than-average temperatures in the same location (a temperature decrease of 1 to 2 degrees below the norm) indicate the presence of La Niña.

La Niña usually follows El Niño as a kind of see-saw effect that transitions as warm waters move west. Cold waters flood the surface, which cools the jet stream and the entire North American continent with it.

“Just in the past two decades, it seems like some of our better winters came with La Niña,” says Scott Braaten, Stowe’s snow reporter, adding that two decades is not enough to form a concrete prediction.

Most meteorological models from climate centers such as NASA, Scripps and NOAA foresee La Niña in our not-so-distant future. But that doesn’t guarantee snow angels and powder-packed weekends.

“La Niña’s a tough one, because it’s gone both ways,” Fox notes. “There have been La Niñas that have resulted in some awful winters, and there have been some others that have been terrific winters. It really is a mixed bag.”

Eric Kelsey, the research director at Mount Washington Observatory, agrees that it’s more complicated than the simple conclusions we tend to make with El Niño and La Niña, a cycle known as the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO). El Niño doesn’t always imply warm weather and a La Niña winter may not be cold—there are too many other factors, especially on the East Coast where we’re a long way from El Niño’s epicenter.

Eric Kelsey, the research director at Mount Washington Observatory, agrees that it’s more complicated than the simple conclusions we tend to make with El Niño and La Niña, a cycle known as the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO). El Niño doesn’t always imply warm weather and a La Niña winter may not be cold—there are too many other factors, especially on the East Coast where we’re a long way from El Niño’s epicenter.

“ENSO is so far away that the effects of it, by the time it gets here, aren’t very consistent,” Kelsey says. “Very small changes in the storm track—we’re talking a hundred miles—can make a very big difference in how much snow you get, or if you get more snow versus rain, so there are lots of little details that can have a big impact on snowfall.”

What can we count on, then, to bring us the cold and snowy weather we crave?

Kelsey says a more reliable indicator is the Arctic Oscillation, a halo of wind that blows in a clockwise direction around the Arctic at about 55 degrees latitude north (roughly the latitude of the Gulf of Alaska, northern Newfoundland and northern Scotland).

The AO has two phases: a positive phase in which cold weather is trapped within its bounds, and a negative phase in which colder air percolates south. The AO’s negative phase is more likely to bring Vermont an abundance of that light airy powder that’s been dusting our dreams, but the AO varies on a weekly basis, and Kelsey can’t say whether we’ll catch a glimpse of its negative phase this winter.

Fox is following a different climate pattern: the Pacific Decadal Oscillation. It’s described by NOAA as “El-Niño-like,” but PDO affects temperatures in the mid-latitudes, whereas El Niño affects areas near the equator. Right now, the PDO is in a positive phase, which loosens the bounds of the jet stream, allowing cold air to flow toward the east. Fox says the PDO could change, but it’s a more constant factor than the Arctic Oscillation.

“It is very important as far as our ability to access cold weather to have the jet stream in the Pacific stay loose,” Fox said. “The pattern supports relatively good weather.”

New England Cable News meteorologist Tim Kelley, on the other hand, is following the day-to-day cold and warm spots that are popping up around the globe.

Kelley says Canada and Greenland have been sporting some cold weather. For example, during the second week of July, snow fell in Idaho, Montana, Washington, Italy and in Austria the snowline cascaded below 5,500 feet.

“So that’s the equivalent elevation of Mt. Washington,” he says. “That is wicked cool, I love to see that.”

These events don’t indicate anything concrete, he admits, but keeping track can give us an idea of how weather systems are stacking up.

“I’ll never forget four summers ago how cold it was in Canada,” he says. “I saw it snowing in Canada in July and August, and thought ‘Gee, I’ve never seen it like this before.’ Sure enough, the following winter, (three winters ago), Michigan had its coldest winter on record and Lake Superior froze more solidly than it had in a century.”

Kelley says the cooling Pacific will also play a role in a colder winter. In early August, the eastern Pacific was less than 20 degrees Celsius, or 68 degrees Fahrenheit, and up to 2 degrees below average.

“That the Pacific is colder is a huge factor,” Kelley notes.

As of late October, Kelley is confidently optimistic about this winter’s outlook. With widespread snow across nearly the entire northern hemisphere, a negative phase of the Arctic Oscillation and Vermont’s best October snowstorm in seven years, we’re headed far from the warm conditions that plagued last season.

“The entire nation should have a colder winter than we did last winter. The Atlantic Ocean is still kind of warm, which is good, because you want moisture. You want to keep the moisture supply and you want the air to be colder.”

More moisture, colder air. If only we could whisper into the ears of the snow gods. Maybe it will happen—maybe the stars (or should we say “snowflakes”) will align and give us La Niña, or a positive PDO, or a Pacific Ocean that continues to cool.

But for now, we can only do our snow dances, wear our jammies inside out and have faith in Mother Nature.

photo by Brian Mohr/EmberPhoto