5 Legendary Vermont Ski Lodges

Across Vermont, classic ski lodges are being restored, bringing back an era of good times.

By Lisa Lynn

Even before there were lifts in Vermont there were ski lodges, places early skiers bunked at while they explored the mountains—places like Stowe’s Green Mountain Inn or Waitsfield’s Tucker Hill Inn. Some actually gave rise to new ski areas and changed skiing. Johnny Seesaw’s was one of those. And now, thanks to local skiers Ryan and Kim Prins and their business partners, Seesaw’s Lodge is back.

The legend of Johnny Seesaw’s starts like this: In 1924 Ivan Sesow, a Russian immigrant and logger, bought a parcel of land near the base of Bromley Mountain in Peru, Vt., with views to Stratton Mountain, for $300. Sesow, a logger by trade, hewed trees on the property and built a large log cabin (which he dubbed the Wonder View Pavilion), as a dance hall, with “sin cabins” out back. With a bandstand in one corner, it gained notoriety, especially during Prohibition as his second wife, Vinnie (a local girl Sesow married when he was 33 and she was just 14) served homemade wine and moonshine she distilled. The place was largely disreputable and wildly popular. After Prohibition it fell on hard times. Sesow lost the Wonder View and it fell into disrepair.

From Wonder View to Johnny Seesaw’s

This season, something old is new again. Skiing down Bromley you can take a side trail through the woods and end up at an old sugar shack. Decades ago, sap was collected and boiled into syrup right in this structure. In 2019, it has been transformed it into an apres ski spot where you can warm up by the wood stove, grab a hot drink and snacks or head outside to gather around the firepit at Seesaw’s Lodge.

In early 1938, Fred Pabst (of the Pabst beer family) set up a small rope tow just up the hill on Little Bromley. Ski instructor Lew de Schweinitz and his brother-in-law Bill Parrish made a deal with Pabst that “if de Schweinitz bought the Pavilion and turned it into a ski lodge, Pabst would put up a rope tow in the West Meadow,” on Bromley Mountain, wrote Parrish’s godson, Jackson Hogen, in a 2004 article in Skiing Heritage. The deal was done and the Bromley Mountain Ski Club, as Johnny Seesaw’s (nicknamed for Ivan Sesow) was officially named, opened the day after Christmas, 1938.

“At first, my father and mother invited their friends to come stay,” remembers Alan Parrish, Bill’s son, who grew up at the lodge and still owns an adjacent house. “Then skiers started coming back year after year. It got so popular my parents made a policy that you had to know someone and have a good reference to get a reservation.” The lodge hosted a who’s who of skiers and celebrities. “Charles Lindbergh and his wife [Anne Morrow] stayed here to get away from all the publicity after their son was kidnapped,” Parrish recalls. National Ski Patrol founder Charles “Minnie” Dole and some friends dreamed up the idea of the National Ski Patrol there over drinks in 1940. Other guests included Gerald Ford and Yale president Kingman Brewster, along with various Kennedys and the Harrimans.

Dinner was served in the old dance hall on heavy pine furniture of a Bavarian design and chairs with hearts cut out of the back. After, guests would gather around the circular fire pit with its six-foot copper-clad chimney, which the Parrishes had custom-built and fashioned after one they had seen at Colorado’s Grand Lake Lodge. “John Jay would often come too and screen his films,” Parrish recalls, remembering the man Warren Miller credits with inventing the ski movie.

“One thing my parents were concerned about was that their guests didn’t get hurt skiing, so my father invested in skis and the early safety bindings,” Alan Parrish remembers. Bill Parish had served on the board of Ski Industries of America and helped bring about an early study on ski safety that “showed that at the time [1958] a ski injury cost the industry $5,000 in lost lodging, meals and equipment sales,” Hogen wrote. Bill Parrish began importing Aluflex metal skis from France with more modern safety bindings and wooden Amori skis from Japan. “He’d heard about Clif Taylor’s approach of using shorter skis and his book Ski in a Day so he took those old seven-foot Amori skis and cut them down to 39 inches and they worked great.”

Parrish went on to become an engineer and invented the device and systems that have helped measure the hole in the ozone layer above Antarctica. The Parrishes sold the inn in 1974.

In 1980, Gary Okun, a lawyer from New Jersey and his wife Nancy spent five days as guests at Johnny Seesaws and offered to buy it that same week. In 2008, the place was named to the National Historic Register.

Recovering History

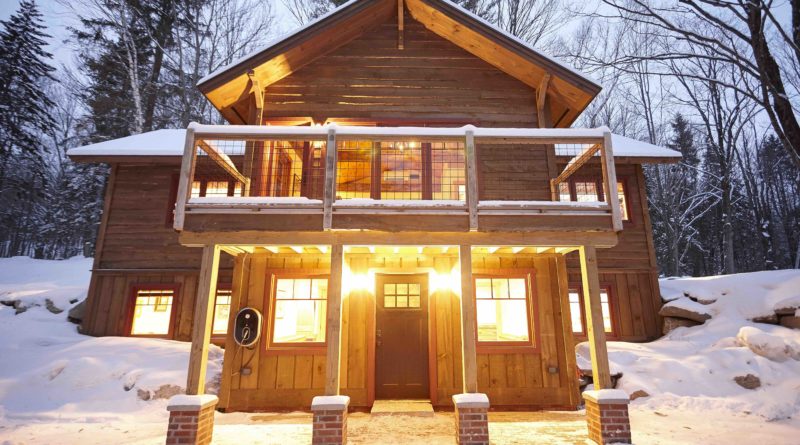

“We would have loved to keep it as an historic building but so much of it was gone that it needed a total rebuild,” says Ryan Prins, as he stands at the doorway of the lodge he and his wife Kim have spent two years of their life lovingly recreating.

Prins, originally from Curacao, had grown up skiing at Stowe. He and Kim and their two kids had been living in Arlington and were looking at buying an inn. “We were looking everywhere from Stowe to Alaska,” he says. He heard Seesaw’s was going up for auction in 2015 and went, fully expecting an out-of-state bidder who had shown some interest to bid high. “He wasn’t even there at the auction—hardly anyone was there,” Ryan recalls. The Prins bought the seven acres, the lodge and its various outbuildings for $155,000.

Then the work started. While others might have either patched things up or razed the place and built something new, the Prins (who ended up partnering with the gentleman expected to buy it, a person who was very familiar with the lodge’s full history) went about meticulously dismantling the old log lodge and reassembling it, piece by piece. The logs were cleaned and set back in place, the “Seducerie”—the site of the old bandstand—taken apart board by board, its mural meticulously restored. It now serves, along with the old library, as a quieter place to take meals.

Old bureaus were fashioned into cabinets in the pantryways. The Parrish’s old pine chairs and tables were lovingly refinished. And the centerpiece—the circular fire pit—was put back in place along with another fireplace. Equidistant from that fireplace another fire pit was installed outside near a skating pond and warming hut.

A large lodge out back (what was once the old ski barn) has a great room with a fireplace, kitchen and guest rooms, each named for a local hardwood (Cherry, Oak,

Beech, etc.). And old “sin cabins” and a chicken coop have been beautifully restored as guest suites with original wood paneling (“some of it still has the old graffiti etched in it,” Ryan points out) and bureaus. With kitchens, stoves and two or three bedrooms each, they are furnished in an clean, simple style. Work from local artists hangs on the walls. In the lodge, Ryan points to two heavy pine sled chairs, “We found these out back and refinished them.”

It took a phenomenal labor of love, not unlike the love that the Parrish family lavished on the place back in the 1930s. In a nod to Vinnie Sesow, the Prins plan to put a distillery in and brew their own “moonshine.” And like the Parrishes, last year they lived on the property and invited their friends to come stay, “our ‘soft opening’” says Kim.

This season, Seesaw’s is open to the public. However, unlike in the Parrish era, you no longer need to know someone or have a reference to stay. Rooms start at $299 a night. seesawslodge.com

The Valley of Lodges

BY ABAGAEL GILES

In today’s world, where hotel chains are widespread and independent ski areas are rare, the Mad River Valley offers something unique: a wide array of historic ski lodges, many restored as boutique inns. Each is different, but all of them have tapped into the Valley’s eclectic history and traditions of warmth and community. At each of these iconic ski lodges, good food, good people and good design meet to offer something that feels true to the heart of what skiing once was.

The Hyde Away, Fayston

The Hyde Away Inn is a true mainstay of ski history in the Mad River Valley, dating back to 1949 when it first opened as the Ulla Lodge, named for Ullr, the Norse god of snow.

The original farmstead once housed a clapboard mill that, in 1889, churned out 700,000 clapboards per year. Brothers Sewall and Arthur Williams converted the farmstead to an inn and began operating it as the Ulla Lodge in 1949. Sugarbush founders Sara and Damon Gadd bought the lodge in 1954 and had dorms for men and women.

In the early 1970s, Ulla Lodge was sold and became the Snuggery Inn and raucous Zach’s Tavern. The California hot tub, an object of après ski infamy, sat in the farm’s silo during this period. The complex was purchased and renovated by Bruce and Margaret Hyde in 1987 and renamed the Hyde Away Inn and Restaurant. After 28 years, the Hydes sold the Inn and Restaurant to current owners Ana Dan and Paul Weber in 2015.

These days, guests can choose from a variety of modern rooms, from spacious suites for families, to retro ski dorms over the bar, to the Hyde Away House. With Heady Topper and other Vermont microbrews on tap, the Tavern is the perfect place for an après-ski game of pool or to have a drink by the fireplace. The food ranges from entrees featuring local meat like the bacon-wrapped Vermont-raised meatloaf, to excellent pub fare like the Neill Farm beef burger with house aioli, all prepared by executive chef Chris Harmon.

Though the hearty breakfast and historic silo may make you feel like you’re staying in a farmhouse, the Hyde Away is hip. This is a great place to find the newest microbrews or to slip away for a classic Vermont ski vacation with all of the local flavor you’d expect from the Mad River Valley. Rooms start at $99 per night. hydeawayinn.com

The Mad River Barn, Waitsfield

At just 1.7 miles from the base of Mad River Glen, Mad River Barn is an icon. The Barn was the brainchild of Mad River Glen founder Roland Palmedo, who convinced a few friends to buy the property. The crew put in a pub and a huge stone fireplace, a bunch of stuffed caribou, moose and bear heads, and called it “The 19th Hole.” They used to ski to the barn on an unmarked trail for après-ski parties.

However, the barn’s humble origin lies with the Civilian Conservation Corps, for which it served as a bunk house in the 1930s. It was first converted into an inn by Les and Alice Billings in the 1940s or 1950s.

In 1975, Mad River Glen’s legendary former owner Betsy Pratt took over operation of the Barn, after the death of her husband, Truxton Pratt. Pratt, who ceded Mad River Glen to a cooperative of skiers in 1995, sold the Barn to current owners Andrew and Heather Lynd in 2012. Pratt had meticulously preserved the Barn’s original character, which Ski Magazine called “the coziest barn you’ll ever sleep in” in 2010, in keeping with her friend Palmedo’s original aesthetic. In 2013, the Lynds set out to update the plumbing, commercial kitchen, beds and other infrastructure, while preserving that character.

Today, the Barn’s rooms feature white walls, big windows, sliding wooden barn doors and elegant, clean lines. Additional rooms are located in The Annex and Longhouse, with wrought iron lamps, bed boards made of reclaimed and finished wood. The beds are made to look as though they are still propped up on wooden crates—as they once were.

The restaurant and pub feature wood floors, the same classic stone fireplace, exposed wood walls and a sleek, grey bar with warm lighting. The dining room has long, rustic wooden tables and local fare like Vermont-raised elk and venison stew.

Pratt famously told The New York Times in a 1989 interview, “I’m not a member of the ski industry. I’m a steward of a mountain.” That legacy lives in the walls of the Mad River Barn. Rooms start at $160 per night. madriverbarn.com

Tucker Hill Inn, Waitsfield

In its 70 years of operation, the Tucker Hill Inn has launched its share of ski bum-turned renowned chefs. American Flatbread chef-owner George Schenk got his start as a line cook at the inn’s restaurant in the 1980s, alongside three-time James Beard Cook Award-winner Gary Danko.

When it first opened in 1948, Tucker Hill had a 600-foot tow rope in the backyard and a handful of ski trails behind the lodge. That was the same year Mad River Glen’s lifts started running, and Tucker Hill claims to be the first lodge built to accomodate skiers in the Mad River Valley.

Today, Tucker Hill Inn still feels like a ski lodge. The yellow, Colonial-style house features 17 rooms, some with floor-to-ceiling fireplaces and marble-tiled floors and others furnished in a rustic style, with bunk beds and wrought iron bed frames.

Current owners Kevin and Patti Begin purchased the property in 2015 and reopened the restaurant and pub, which had previously been closed, in 2016. The restaurant offers fine dining in a cozy, firelit environment while the pub has a beautiful exposed-beam bar, cozy armchairs and a deck with a great view. “The stairs are narrow and steep, so you feel like you’re descending into a speakeasy,” says Kevin.

“It feels like a local place that happens to be available to tourists when they’re here,” adds Begin of the pub’s atmosphere. Rooms start at $139 per night. tuckerhill.com

Lareau Farm Inn, Waitsfield

In the late 1980s, George Schenk was skiing up a storm and cooking at nearby Tucker Hill Inn when he started experimenting with baking flatbread appetizers under the stars in a homemade wood-fired oven of stacked fieldstones. His flatbreads were so popular that in 1992 American Flatbread opened in the Lareau Farm’s iconic barn and in 2001 Schenk bought the farm and inn.

Lareau Farm was first built in 1794 by Simeon Stoddard, a friend of Waitsfield founder Benjamin Wait. When it was converted to an inn in 1982, the idea was to create a simple but classic Vermont ski lodge with a unique farm-to-table breakfast and all the comforts of a traditional farmhouse. Today, the white-clapboard bed and breakfast sits on a 24-acre farm and features just 13 quiet rooms.

Last year, the inn began redecorating and modernizing its rooms, which feature hardwood floors, wrought iron bed frames and white linens. “There are no TVs and we aim to create a simple, quiet experience,” says Clay Westbrook, general manager. “We now see people who came here as children to ski bringing their kids,” he says.

The complimentary breakfast includs eggs from the farm’s chickens, bread baked in-house and sausage and bacon raised and cured on-site

Owner Schenk has stayed true to his ski bum roots. Look for him hosting The Big Kicker, Sugarbush’s annual rail jam and opening party at American Flatbread each November, or skiing at Sugarbush.

The best perk? Lareau Farm Inn guests get priority for reservations at American Flatbread, which still serves the same wood-fired pizza it did in 1992, featuring ingredients grown right on the farm. Rooms start at $101 per night. lareaufarminn.com

Your history of the Mad River Barn is wrong. You should get your info from people who live in the Valley and were there when events happened.

Steve, could you let us know what was incorrect? Thank you. Lisa