Bud Keene Will Push You to Greatness

One of the most successful snow sport coaches of all time, Bud Keene focuses on progression in athletics and life.

By Lisa Lynn

Backstory: There is a boy. He is 13 years old. He sits at home in Virginia Beach, Va., reading about mountains and those who climb them. It is the 1970s. Italy’s Reinhold Messner is climbing the Eiger in Europe and making first ascents in the Himalaya. American Ned Gillette is circumnavigating Denali and Mt. Everest.

The boy is one of seven children. His parents are not adventurers, but they take the kids camping and hiking in the Shenandoah every year and, once, to Killington. The boy plays lots of baseball, and sometimes surfs and skateboards. He dreams of building a log cabin in the mountains and of spending his days climbing peaks.

At 19, he follows his father’s path and enlists in the Navy. He is a good sailor, finishing out his enlistment, and he excels at celestial navigation. But it is not what he wants to do.

He tries college, studying engineering at Virginia Tech. He moves to California’s Russian River Valley for a bit, before moving back home.

This does not quite work out either.

One of his sisters is a successful fashion designer. One day the two sit down and make a list of all the places they would like to live: Paris, Monte Carlo, and other exotic destinations, including one place they can actually afford, Stowe, Vt. They move there. He gets a job as a chef’s apprentice, and spends three months learning to ski. It is December 1983.

In February, after seeing a man named Lowell Hart walk through town with a snowboard on his back, the boy pleads with Lowell to take him up on the mountain. The next day, the boy buys a Burton Woody Performer. It has a wooden base, no edges and aluminum fins. Snowboards are not allowed on the mountain, so he hikes up and gets chased down and hikes back up again and gets chased. Pretty soon, the boy figures it out: This, this is what he wants to do.

Robert “Bud” Keene is 55, 5’6’’ and built like a spark plug. His face and hands are those of a man who has lived outdoors for much of his life and there is something about him that makes you realize that if he wanted to, no matter your size or age, he could kick your ass.

When he looks you in the eye, you don’t look away; he won’t let you. “As a coach I have a reputation for being intense and I don’t necessarily mind that,” he says, his blue eyes staring—not at my chin or hands or shoulders—but right in my eyes in a slightly uncomfortable way. He hedges, and then says with a grin—eyes now twinkling like blue ice crystals— “But I’m also present, like I really care. Which I do.”

He glances away. “Some other coaches will kind of nod, hide behind their dark glasses or give advice without really connecting. They might let a kid look at his shoes and say, ‘Ok, yeah, yeah…I know, ok.’ But I need to see people’s faces and just as importantly let them see mine, to make sure that we are relating and that they know what they have to do.”

And that’s one reason why his nickname, “Bud,” just seems to fit.

Bud is sitting at The Whip in Stowe. His stubby, gnarled fingers—fingers that have worn Olympic rings and pulled him up the stony face of El Capitan—are wrapped around a cold glass of beer. The server recognizes him. “Hey, isn’t that Shaun White’s coach?” he whispers when Bud gets up.

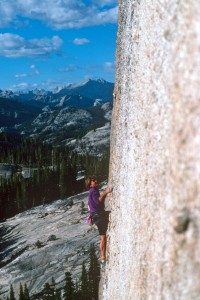

Bud is happy and relaxed. It is August and he is back from a week of climbing with his eldest son, Zak, 23, in Yosemite and the Sierra. “We did a lot of technical stuff. I wanted to show him the first ascents and routes I did when I was his age.” They also did the less-technical Mountaineer’s Route on Mt. Whitney. He pulls up an app on his iPhone. “See, we did 46,264 steps—that’s 474 flights of stairs—and covered the 20 miles in 9 hours.”

Much of July, Bud was at his day job: coaching the next Shaun Whites, Louie Vitos and Jake Blauvelts at the BKPRO snowboard camp at Mt. Hood.

This is what he does. And he does it better than anyone in the world.

Bud Keene is one of the winningest coaches in snow sports history. Since 1989, when he started the snowboarding program at the Mount Mansfield Ski Club, he has worked with riders such as U.S. Open winner and big mountain rider Jake Blauvelt; Kyle Clancy, who went on to podium in pretty much every snowboard discipline; Thomas O’Brien, a World Cup-winning racer and member of the first-ever U.S. Snowboard Team; Travis Kennedy, Colin Langlois and others—all current or past top sponsored pros. Bud went on to be an assistant U.S. Snowboarding Halfpipe coach at the 2002 Olympics where the American men took all three medals and Kelly Clark, of West Dover, Vt., won the gold.

He was promoted to head coach in 2003 and worked with a small dream team of athletes preparing for the 2006 Olympic Games in Torino, Italy. Among eight of them, they took home two golds, two silvers and two fourth places. That spring, he was invited to Washington, D.C., where the U.S. Olympic Committee gave him its highest honor: National Coach of the Year.

In Torino, Bud put the world on notice and launched his young medalists— Shaun White, Danny Kass, Gretchen Bleiler and Vermont’s Hannah Teter—into stardom. But once the games were over, Bud was ready to dial it back and spend more time with his family in Stowe. He left his U.S. coaching role, announced his retirement and went home to his wife and two sons, then ages 14 and 9.

Home wasn’t what it had been. He and Lucie, his wife of over 20 years, broke up. Not long after, Bud reconnected with Shaun White.

It is 1985, the boy is now good at snowboarding. He loves to cook and has a good job as a chef’s apprentice at Stowe’s Topnotch Resort.

He reads Outside and sees a notice from adventurer Ned Gillette, who is taking applications to join a crew in his expedition to be the first to row from South America to Antarctica across Drake Passage, the roughest body of water in the world.

The boy tells a local friend and bartender about this. “Ned lives in Stowe, you know,” the bartender tells him. The boy is stunned. He calls Ned Gillette. He tells him about his time in the Navy and how he knows celestial navigation. There is a long silence. Finally Gillette says, “I don’t normally do this, but I will meet with you.”

Gillette begins their meeting by saying flatly, “You’re a nice guy, but you’re not coming on this trip.” Still, something impresses him about the kid, and so he offers to allow the boy to help in setting up logistics and running errands for the expedition. One day, Gillette tells him to take his Saab with the rowing shell and go practice. The shell and the boy come back in one piece. After two months of this Gillette unexpectedly drops a bomb: The boy, 26, is now on the team with Gillette and two others.

They fly to Patagonia and wait for a month for the conditions to be right for a crossing. In the meantime, they paddle the fjords, climb and bathe in icy falls. The conditions, radioed to the group by weather forecaster Bob Rice, keep coming in as “red alert – don’t go.” An orange signal means “get ready,” and green means “go.”

The forecasts are all red, the wind and the currents are too strong. One day, running out of time for an attempt, the crew gets antsy so they head out anyway. The boy’s snowboard is strapped to the boat as he also plans to be the first to ride Antarctica.

The boy sees waves he thinks must be 40 feet high, the 28-foot open-cockpit rowboat, the Sea Tomato, gets rocked and rolled. It is all they can do to get back to safety. They will try again next year, Gillette assures the team.

But by the time they do, the boy has gotten his first snowboard sponsorship with Sims. He chooses snowboarding. Gillette does the passage without him.

Two years later, in 1988, the boy, his wife Lucie, Lowell Hart and Jim Martin head back to South America. This time, they are there to be the first to snowboard the highest mountain on the continent, 22,834-foot Mt. Aconcagua. They set the world record for the highest altitude descent by riding down from over 22,000 feet.

By the 1990s, he is back in Stowe, coaching at Mount Mansfield. He coaches Jake Blauvelt who, in return, lets him fell trees on his grandfather’s property. Using those trees, the boy, now the man everyone calls “Bud,” builds his dream house: a log cabin.

Everyone knew there was something special about Shaun White, even before the 2006 Olympics, but no one so much as Bud, who had begun working with him one-on-one in New Zealand in 2005. “I can’t say what it is, but when you see talent, you know it,” Bud says. “It’s just my job to help that talent progress.”

Bud had gone back to the U.S. Team as the freestyle development coach and he proposed to continue to work with Shaun as his personal coach.

With Bud at his shoulder for weeks on end, Shaun kept on upping the ante, not only for himself, but for snowboarding as a whole. At the 2010 Vancouver Olympics, Shaun had sewn up the gold medal after his first run with a record-high score of 46.8 out of 50. He didn’t even need to do the final run, but as Shaun stood at the starting gate, Bud goaded him. “You can go out there and run it straight,” he said, nonchalantly. “Or you can f-ing stomp it!” (unbeknownst to Bud, a camera microphone broadcast his f-bomb on live TV).

Shaun stomped it, throwing a crowd-raising first-ever Double McTwist 1260 at the end and earning the highest score ever in Olympic halfpipe snowboarding: 48.4 out of 50.

What could come after that? Perhaps the biggest challenge for any coach is to help a superstar continue to improve. As part of his current job with the New Zealand team, Bud has to forecast four years out what the next winning tricks and runs are going to be.

“When I was competing, the hardest trick in the world was a 540. Then it was double corks, then triples, and now even quads,” Bud says. “The training gets more intense, the gymnastic element more demanding, the jumps get higher and the penalties for failure more profound.”

Going into the 2014 Sochi Olympics, Bud and Shaun worked hard on a new trick: the triple cork 1440—four complete rotations while flipping off axis—sort of like a spinning planet in orbit. While Shaun could land it in open course slopestyle and on airbags, two of his attempts to land one in the half-pipe resulted in injuries.

After that, as the documentary “Russia Calling” shows, Shaun was painfully unable to pull one off. The film, produced by Shaun, shows Bud cheering him on, dousing him in Lake Tahoe’s frigid waters (part of Bud’s signature ice water bath therapy), feeding him smoothies and telling him he can do it. It also captures Bud muttering to himself and Shaun crying in frustration on his shoulder.

In the film, Shaun tries and tries to launch the triple as a million dollars worth of cameras and film crews wait patiently, but he just can’t. “It’s hard to show up at the mountain and have somebody go ‘are you ready to do this trick?’ The same trick that the first time you tried it, it put you in the hospital and the next time you tried it you nearly cracked your pelvis,” Shaun says to the camera.

“There’s a saying by Henry Ford,” says Bud. “Whether you think you can, or you think you can’t, you’re right.” He pauses. “I’m not someone who takes unnecessary risks. When I try something or ask someone else to, I know all the elements. I think things like cliff diving are scary as hell. There’s no practice, there’s no coaching, there’s no landing pad.”

Shaun and Bud spent seven weeks practicing the triple cork on air bags in a private pipe in the Sierra before the camera crews showed up. Shaun had it nailed on the air bag. It was just a matter of doing it on snow.

“When I say ‘red’ it means a kid is not ready for a trick,” says Bud. “But if I say ‘it’s all green,’ it means the conditions are right and you’re ready for it.” Shaun had a green light then, and at the Sochi Olympics. In Sochi, he dropped out of the slopestyle and finished fourth in the halfpipe.

“Shaun and I, we’re taking a break now, just like we always do leading up to a Games,” says Bud. In the meantime, he’s been busy working with other athletes such as the 2014 ski slopestyle Olympic silver medalist Gus Kenworthy, and the New Zealand National Team, including the famous Wells brothers.

The “PRO” part of Bud’s BKPRO camps stands not for “professional” but for “progression,” and that is what Bud looks for. At the BKPRO camp in Mammoth this past April, 22-year-old Yiwei Zhang (whom the Chinese Ski Association plucked out of a gymnastics class at age 11), became the first person to land a cab triple cork in the half-pipe. It didn’t hurt that he idolized Shaun White, trained with Bud and had been studying Shaun’s video footage.

“I’m not necessarily for turning gymnasts into snowboarders,” says Keene, acknowledging a trend that’s happening in China, Brazil and other countries. “But I’m all for seeing snowboarders learn more about gymnastics. After all, look at any gymnastics comp: you have these 13-year-old girls doing triple corks off the mat. And they stomp it in their bare feet!”

It is winter 2011, and Bud is at the X Games in Aspen with his fiancée, Alexandra Sharpe, a blonde British beauty who is the spa director at Topnotch in Stowe.

“When I met Bud in 2010 he was taking a break,” she says. At the time he had returned to Stowe to work with his brother at his car dealership in Morrisville. He saw her glance at him at a bar, asked her out the next day and they were married 11 months later. “I didn’t snowboard and I had no idea who he was in that world,” she remembers.

Bud is remarkably good at keeping his accomplishments to himself. Few in the snowboard world know of his climbing skills. Not all his climber friends know of his snowboarding.

In Aspen, they walk down to the street and are instantly mobbed. “Bud isn’t wearing his gear or logos, but people recognize him and they just keep swarming him,” Sharpe says. “At one point Norwegian Olympic medalist Kjersti Buaas comes up and throws her arms around him and says to me, ‘Bud is our spiritual leader.’ She is not even someone he is coaching — she’s speaking for the entire international freestyle community.”

Later, after watching the halfpipe, the two head to the beginner slopes and there, the man who coached so many Olympians, begins to teach his future wife to ride.

“You know what I like to do best now?” asks Bud. “I’m happiest just snowboarding down a bunny slope with Alex and watching her get better. It’s really not at all about winning. My goal is to simply help people do what they want to do. Coaching—and life—are all about progression.”

Watch Yiwei Zhang do a triple cab cork at BKPRO at