Ski historian chronicles New England’s lost ski areas

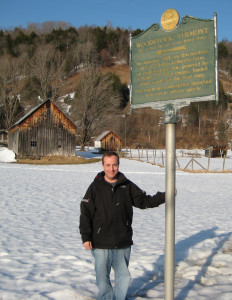

Jeremy Davis, founder of the Lost Ski Areas Project, has dedicated his research to discovering New England’s abandoned ski areas.

By Evan Johnson

Ever skied Wildwood Valley? Buckturd Basin? How about Peru Mountain? You’re not alone, if you’ve never heard of these.

It’s hard to believe, but from the 1930s into the 1970s, Vermont had far more slopes (over 100) and for ski-historian Jeremy Davis, these areas are modern archeological sites.

Davis could rattle of a list of these areas all over the Northeast, not solely Vermont. As the Northeast’s premier ski historian, collecting maps, records and personal accounts of these areas has been his passion for more than 15 year as the principal curator of the New England Lost Ski Areas Project.

Born in Chelmsford, Mass, Davis started skiing late in his childhood at the age of 11 at Nashoba Valley Ski Area, a small area with a vertical drop of only 240 feet. Later, he began making ski trips to northern New Hampshire with his family. It was on one of these trips, a young Davis passed by Mount Whittier, an abandoned ski area near North Conway.

“It was something really cool, that there was this big mountain with a lot of abandoned trails and lifts and a lodge that was all boarded up. I was curious to find out what had happened to it,” he recalls. “We saw another area called Tyrol in Northern New Hampshire as well on that trip. I hadn’t been skiing too long, but I just happened to find these places by accident and I wondered what had happened to them.”

His curiosity was piqued.

Over the years, Davis gradually expanded his knowledge of abandoned ski areas. He accidentally came across them while driving and discovered newspaper articles, old brochures and other literature at antique shops. Davis was getting a lesson in history.

In the early-to-mid 20th century, ski culture in Vermont was far different from that of today.

Then, in the 1950s and ’60s, small hills in towns and villages were outfitted with rope tows and tiny areas like the Snow Bowl in Saxtons River, or Sugar Bush (not to be confused with Sugarbush) in East Jamaica operated with a popular following among tourists and locals.

Most of the small areas featured rope tows and a few T-bars run with the help of Yankee ingenuity and jerry-rigged engineering. The rope tow at Brownell Mountain in Williston was powered by a Volkswagen Beetle, which was flipped on its side. The operator supplied power by using the car’s transmission to drive the back axle, which turned the rope.

“The vast majority of areas were quite small and certainly not what anybody would consider a resort,” Davis says. “Most of them were small community areas and only really for people that lived within 10 or 20 minutes of the ski area.”

Davis says the height of Vermont ski areas was in the 1969-1970 season, with 100 operations providing service. After then, the number started to drop off precipitously.

A main reason for this decline, he says, was a lack of community support.

Once a town stopped supporting [an area], that was often the death nail,” he says. “Those places ran off of blood, sweat, tears and donations and if people stopped skiing there, that could easily result in its closing.”

Other reasons for closure included inability to expand and cut new trails or failure to construct snowmaking equipment. It was the rope tow that brought skiing to the masses, but consistent grooming and snowmaking allowed larger resorts to smother the competition. While Stratton, Stowe, Sugarbush, Okemo, Mount Snow or Killington were hitting their stride in latter part of the 20th century, more and more small areas closed every year.

Everyone needs a hobby, and Davis continued his research well into college at Lyndon State, when he started the New England Lost Ski Area Project, a clearinghouse for information on the more than 400 resorts in New England alone. Davis says there are tens of thousands of people interested in collecting and preserving skiing history. The motivation behind setting up the NELSAP site 15 years ago, he says, was for collaboration of resources.

“I knew people out there had more information than I had, that the information was out there, it was just a matter of finding it,” he says. “When I started the site, my hope was that by sharing what I knew, people would start to share what they knew and that’s exactly what happened.”

The result, he says, was astounding.

“The biggest thing I found was the sheer number of lost ski areas in New England. I thought I was going to find a couple hundred when I started and even that, I thought, was pushing it. I never could have imagined there would have been almost 625 that were found. I don’t think anyone had any idea it was that many.”

Davis says the response to the website has been overwhelmingly positive and that he’s been able to tap into “a nostalgia” that many find appealing. He continues to receive testimonials from readers describing their favorite places. He’s also received encouragement to continue his project from the Vermont Ski Museum in Stowe, where he has served on the board of directors since 2000 – the youngest person to be nominated for the position.

Davis lives and works in the Saratoga Springs area of New York as a meteorologist. Working for a 24-hour operation, he says, makes for a different work schedule, but he is able to make it work to his advantage. For one, while everyone else is stuck in the office, he can make midweek turns at nearly empty mountains.

“You get spoiled,” he says. “I went skiing at Stratton yesterday and it felt like a private area. I don think there were 200 people there.”

He says his work schedule also allows him time to develop the site and add material that is constantly coming in while he has energy.

He is also the author of three books, Lost Ski Areas of Southern Vermont, Lost Ski Areas of the Southern Adirondacks, Lost Ski Areas of the White Mountains and the forthcoming Lost Ski Areas of the Northern Adirondacks, due to be released next year.

Most of Vermont’s lost ski areas continue to sit idle and most have no plans to reopen again. However, that doesn’t prevent him from speculating as to how skiing culture in the northeast would be if they had held on.

“It would have been interesting to see what could have happened if more of them had made it to this time,” he says. “You can wonder what would happen to an area like Hogback or Dutch Hill. With social media, could they have gotten the word out on how cool their skiing was and how you didn’t need a huge vertical drop to have an awesome time?”