Skiing Morocco

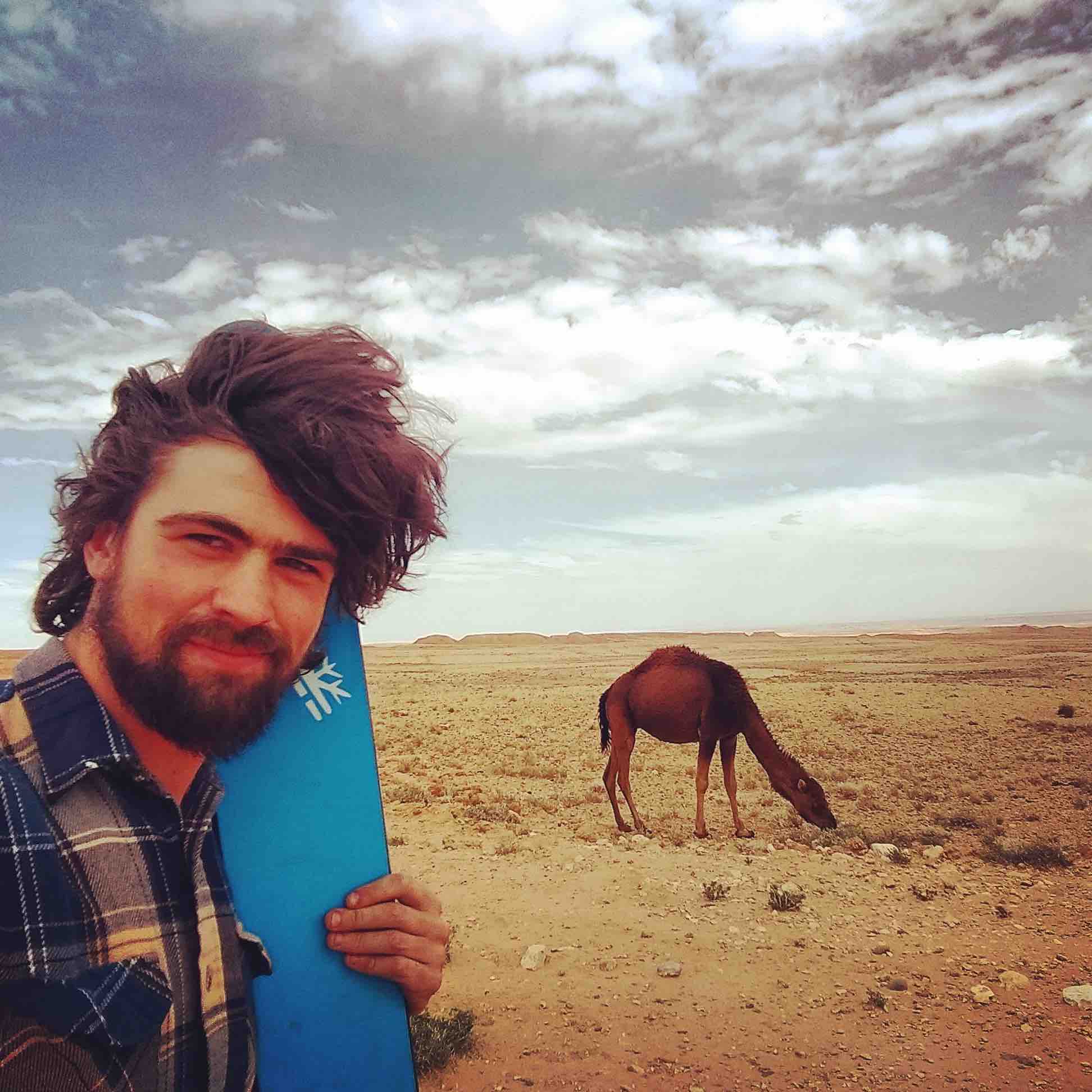

Aaron Gould-Kavet grew up in Williamstown, Vermont, ski racing at Mt. Mansfield Academy and later working several years on dispatch at Stowe Mountain Resort. He will be screening his film “Amazigh” about his adventures backcountry skiing and exploring the local mountain culture in Morocco and serving a Moroccan dinner and cooking class at O’Maine in Portland, ME, on March 30, at Arts Riot in Burlington, VT on April 10 and at Zen Barn in Waterbury Center, VT on April 18.

At 5:00 AM on January 9th, 2018, Ahmed and I embarked on our first adventure. Our destination was Morocco’s (and North Africa’s) 4th highest mountain, Jbel M’Goun, a long massif with numerous peaks above 4000 meters. According to Ahmed, “M’Goun” in Tamazight, a native North African language used by the Berber people of the Atlas Mountains, means “someone sitting and enjoying the view.” Although I never verified this claim, I’d like to think that a hiker sat atop M’Goun’s mighty summit thousands of years ago, only to name the mountain after what he himself was doing there.

Up until January, snow had been elusive in the Atlas Mountains, and I was beginning to wonder if it ever actually snows in Morocco. But just as we left for the car, big white flakes began to drift down from above, gently coating the fine leaves of Ahmed’s olive trees. I could feel those butterflies you get in your stomach right before the first run of the season, but these were different this time. I would be making my first tracks on a new continent, reaching the culmination of years of work, and the realization of a dream. But more on that in a minute.

The Atlas Mountains are vast. Stretching from the shores of the Atlantic to the Mediterranean, these mountains span Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia, reaching heights of over 12,000 feet along the way. They are home to millions of species of flora and fauna, forests, caves, lakes, and snow-capped peaks, providing views that befit science fiction movies set in outer-space. The Atlas Mountains are of course also home many people, most of whom are part of the indigenous North African population called the Amazigh (Berber).

Before you can even think of laying tracks on these mighty mountains, there are a lot of things you must first endure. Getting to the base of most mountains in Morocco is a headache of massive proportions: There is no public transportation, so you’re best off renting a car and spending hours dodging children riding donkeys, while trying to pass hay trucks going 15 miles per hour, while getting passed by a 1979 Fiat Spider going 110. If you got through that, you still have to forge rivers and drive for hours on winding, muddy tracks. By the time Ahmed and I arrived in Ait Bougmez, the village at M’Goun’s base, the track was lined with meter-high snow banks on each side. Through the crisp, moonlit night you could see wisps of snow rising from the summits 2300 meters above, the din of murmuring goats mixing with the sound of a nearby stream. After a quick Tagine with our friend Rachid, the alarms were set and I was left to lie dreaming of powder, watching the moonlight reflect off my freshly sharpened edges.

Before you can even think of laying tracks on these mighty mountains, there are a lot of things you must first endure. Getting to the base of most mountains in Morocco is a headache of massive proportions: There is no public transportation, so you’re best off renting a car and spending hours dodging children riding donkeys, while trying to pass hay trucks going 15 miles per hour, while getting passed by a 1979 Fiat Spider going 110. If you got through that, you still have to forge rivers and drive for hours on winding, muddy tracks. By the time Ahmed and I arrived in Ait Bougmez, the village at M’Goun’s base, the track was lined with meter-high snow banks on each side. Through the crisp, moonlit night you could see wisps of snow rising from the summits 2300 meters above, the din of murmuring goats mixing with the sound of a nearby stream. After a quick Tagine with our friend Rachid, the alarms were set and I was left to lie dreaming of powder, watching the moonlight reflect off my freshly sharpened edges.

As it turned out, the snow was terrible, Ahmed hurt his knee, and we didn’t reach the summit. But I was hooked. The Atlas region is the most remarkable place I’d ever skied, with the added bonus of coming back from skiing to fresh mint tea and miraculously spiced Tagine. The terrain is from another world, with descents reaching 2000 vertical meters in the right conditions, passing on the way wild terrain features, such as slot canyons which freeze up and become skiable. But the best thing about skiing in the Atlas Mountains is the people that surround you, the Amazigh. “Amazigh” is the Berber word for themselves, which roughly translates “the free people.” Ahmed Achou, more than anyone I’ve ever met in Morocco, embodies this spirit of freedom which defines his people.

Life in the Atlas

Ahmed grew up in Oulad Ali Youssef, a small village at the edge of the Middle Atlas Mountains, roughly 200 kilometers southeast from the city of Fes. At the time, Oulad Ali had no electricity, and only a rough 4 by 4 track to reach its muddy walls. His father passed away when he was only three, which forced his brother to look for work in the city and send home what little money he could. After completing the 7th grade, Ahmed himself left school to provide for his family, with professions ranging from picking olives to shepherding sheep through the remote steppe which lies above Oulad Ali. In 2005, a flood of truly biblical proportions destroyed his family’s home, forcing the whole family, nearly a dozen people, to live in just a single tent.

However, through it all, Ahmed found sanctuary in the mountains, where the enormous vistas seem to reach out and swallow any earthly problems we might have before us. Perhaps it is, in fact, this feeling for which the mighty “M’Goun” is named. In any case, it was while cleansing his mind in the mountains that Ahmed began to notice the handful of Spanish climbers who had begun to visit the Middle Atlas, and sensing an opportunity, he decided to become a mountain guide. Just a decade later, Ahmed taught himself Spanish and French, learned how to climb and ski, and built a beautiful mountain guesthouse called Gite Bou Naceur.

It was here, while gazing at the mighty cliffs above his gite, or guesthouse, that I met Ahmed, and we both knew immediately that we had a unique kind of friendship. We’re the kind of friends that finish each other’s thoughts, that understand what the other is thinking before they even speak. It’s the kind of friendship that transcends even the vastest cultural and linguistic barriers. I had originally come to Morocco to learn Arabic, part of a dream I had while working at Alta Ski Area in Utah. I knew if I actually wanted to ski the goods in the Atlas Mountains, I would need to learn the local language and befriend rural Moroccans, but how I was going to do that remained elusive, that is, until I met Ahmed.

Ahmed doesn’t speak any English, but my broken Arabic which I had dutifully learned was enough for us to communicate. After a single evening, he invited me to come live with him and his family in Oulad Ali Youssef, and I knew right then that something really special was beginning. I realized I wasn’t just fulfilling a dream from my ski bum days in Utah, or finally learning a complicated language I had set out years ago to learn. What was beginning was a relationship with the Atlas Mountains and the people that live there, a much bigger and greater adventure than I couldn’t have ever dreamed of all those years ago at Alta. But that would have to wait, that is, until I finished my studies in Rabat, Morocco’s capital. Six weeks and a big snowstorm later, I returned to Oulad Ali, only to immediately pack the car, and set my alarm for 5:00 AM.

Skiing and Filming in the Atlas

Luckily, my first adventure with Ahmed was far from my last. I would go on to ski every major peak across the Atlas Mountains, as one of the snowiest seasons in a decade brought powder skiing well into May. Sometimes for more than a week at a time, we ventured through the mountains, skiing first descents that tower high above the Sahara. But I was doing little to document all the amazing places I was skiing, so I began exploring the idea of making a new kind of ski movie in Morocco.

I wanted to make a film that both shows the wonder of skiing and riding in this remarkable place, while also providing a platform for the Amazigh people to share their story and their experience living in these mountains. A longstanding frustration I’ve had with adventure films which take place in developing countries is that they often focus on the story of the athletes, while leaving little room for the voice of the people who actually live in the countries they’re visiting. It’s great that so many people from developed countries have transformative experiences traveling to societies different from their own, but the neocolonial trope of Westerners having life-changing travels in Africa has been repeated ad nauseum across all too many types of media.

Unfortunately, few people seemed to understand my idea, and I had just about given up on making a Moroccan ski film this season. Yet to my surprise, Charlie Coquillard, otherwise known as “The Vertical Wanderer,” found some of my snowy pictures of the Atlas Mountains on Instagram and reached out to me. Just a few short weeks later, we packed up Charlie’s van, and began shooting a film unlike any either of us had ever seen. Even now, having completed the film, I still sometimes hesitate when someone asks me what it’s about. It is a film about the Amazigh, mountain tourism, and of course skiing, but none of those things are the essence of the movie. If I had to put it simply though, the film is about our relationship with the mountains, about how we live with the mountains, our place in them, and their place in us.

While working on the film, I indeed asked many of my Amazigh friends to describe their relationship with the Atlas Mountains. Their responses were nearly uniform: “Aalaqt hub” (علاقة حب), meaning “A relationship of love.” Far from jaded, most of the people who call the Atlas Mountains home know that they are the guardians of a very special place. They love these mountains in the way one loves a grandmother, seeing in them a deep wisdom and calm that can scarcely be found anywhere else. These mountains are the place where Ahmed and the Amazigh go to clear their mind, to sing at the top of their lungs, to release themselves from trials of life, and to be at one with nature.

Mountain Tourism and Morocco

The desire to feel removed from civilization is as old as civilization itself. We are seemingly designed to connect with nature, to simply sit and enjoy a majestic view, and to explore the wonder of the natural world around us. However, as cities grow and our societies become increasingly detached from nature, more and more people are traveling to mountainous regions in search of the unique sense of removedness that they provide. Consequently, an entire mountain tourism industry has grown from the peaks of the Himalayas to the floor of the Grand Canyon, hosting millions of visitors annually.

However, these visitors bring the very trappings of modern life they are trying to escape: money, technology, and trash, to name just a few. In turn, mountain communities and mountain environments are being transformed at a rapid pace, in the worst cases leading to the destruction of previously pristine alpine areas. Mountain cultures, preserved in their isolation, are also quickly changing as they come into contact with the outside world.

Simultaneously, there is a considerable need for human development in mountain communities, which necessitates significant investments in basic services and infrastructure. Because mountainous regions are by nature remote, inaccessible, and sparsely populated, carrying out these expensive investments inevitably requires subsidization from the urban population. Consequently, development is often foregone in these regions, leaving isolated mountain communities increasingly left behind.

Balancing the need for human development with that of environmental and cultural protection is perhaps the greatest challenge of our time. The arrival of electricity and plastics, the development of new industries, and the construction of infrastructure will all dramatically impact both the character of rural mountain communities and the fragile environment that surrounds them. At the same time, there is a clear need for economic and human development in these areas, which has recently been exacerbated by the diminishing returns from agriculture and the increasing effects of climate change.

A Threatened Climate

While we were making the film, we experienced the impacts of climate change firsthand. Persistent high pressure left us with the lowest snowpack in 20 years, and when it did snow we faced howling winds, the sky a murky brown from the Sahara’s dust. But for the people living here, climate change is an everyday reality. While conducting nearly 40 interviews throughout the Atlas region, 100 percent of the people I talked to said that the climate in their region had changed significantly in their lifetime. In light of the dramatic changes they described, it’s hardly surprising that there is this level of climate awareness among the Amazigh. Rainfed agriculture has nearly been eliminated, replaced by extensive irrigation. Where the droughts are worst, even irrigation fails to address the lack of mountain runoff which has traditionally watered the farms of the Atlas region. Sandstorms, floods, and erosion are also a threat to many Atlas communities, all of which have increased in frequency and magnitude as the climate warms.

Although mountain tourism poses dangers to both the communities and environment of the Atlas Mountains, there are also ways in which it sustains mountain communities and enables environmental protection. Mountain guides in the Atlas pick up trash, look after forests, protecting them from loggers, and deliver much-needed supplies by foot to even the most remote areas. Meanwhile, many farmers in the Atlas are already facing the choice of migrating and supporting their families or trying to survive off of farms in the mountains which cannot produce food in Morocco’s changing climate. For many in the Atlas Mountains, their livelihoods already depend on mountain tourism, and with this income they support not just their families but also countless members of their communities.

This is where a complicated, if not paradoxical image of mountain tourism emerges, one that this film can only begin to address. Mountain tourism can sustain vulnerable communities, but it can also change them beyond recognition. It can help farmers weather the effects of climate change, yet travel is itself a major driver of greenhouse gas emissions (the global tourism industry accounts for 5.5% of global greenhouse gas emissions). It can incentivize environmental preservation, reducing, for example, overgrazing and logging, but it also brings with it graffiti, trash, human waste and other pollutants. It can sustain traditional artisans, while also changing traditional culture and society.

A variety of factors influence how tourism affects communities, including regulation and public policy, the type of activities the tourists are doing, and the nature of the surrounding economy, but it is the choices of tourists themselves which often determine these impacts. I strongly believe it is the responsibility of those who enjoy the mountains, as I do myself, to ensure their preservation for generations to come. We also hold a responsibility to mountain communities to ensure that mountain livelihoods remain viable amidst the growing challenges of globalization and climate change. In living and working with Amazigh communities across the Atlas Mountains for more than a year, the message I heard was often the same: “We are in love with our mountains, and we are happy to share them with you. In exchange, please help us sustain our communities, and protect our culture and environment.”

Whether or not you think tourism in remote areas is a good thing, the innate human desire to explore and experience nature is bringing many people like myself to the Atlas Mountains. The increasing numbers of visitors to the Atlas region presents both a danger and an opportunity, and a challenge that I hope many actors from both inside and outside Morocco will rise to meet. I also hope that the outdoor sports community sees our film and beings to reevaluate how we view our impact on these types of communities. If we are to continue to enjoy the mountains of the world, we must become responsible users of the backcountry, supportive of rural mountains communities, and leaders in the fight against climate change.

I give my deepest thanks to everyone in the communities I worked in for welcoming me and sharing with me so many intimate aspects of their lives. This is dedicated to them, and the spirit of adventure and love that they carry with them all the way to even the highest summits.

- “Amazigh” Film Screening, Moroccan Cooking Workshop and Dinner. Saturday, March 30th, Portland, ME, Workshop from 1 PM, Dinner and film from 5 PM.

- “Amazigh” Film Screening at ArtsRiot in Burlington, VT, Wednesday, April 10th, Door at 6 PM. $7 Cover. Raffle and full bar will be available.

- “Amazigh” film screening and Moroccan tasting dinner, Zen Barn, Waterbury, VTThursday, April 18th. Dinner begins at 5:00 PM, film at 8:00 PM. No cover.