The First Trailblazers

In the 1930s, armies of men with the Civilian Conservation Corps carved paths through the woods of New England.vWe can thank the early backcountry trailblazers for lines we ski today.

clutched the tattered decades-old topographic map in my mittens, valiantly trying to keep it from being shredded by the wind. I looked at the old map, looked at the mountain, and looked at the map again. As the gusts threatened to knock us to our knees, my skiing partner’s faith began to wane: “Are you sure there’s a trail up here?” he demanded.

Of course, I wasn’t sure. Once again, legend and hearsay were my guide, this time leading me to the top of Cannon Mountain in New Hampshire. I was on a search for one of New England’s ghost trails, the fabled runs cut by the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), the Depression-era jobs program, that were beloved by skiers of an earlier generation. Many of these trails were abandoned when lifts were built on the “other side of the mountain” in the 1940s. But a number of trails survived, thanks to the determined efforts of local skiers who wanted to preserve their favorite stashes.

On this day in the late 1980s, I was looking for Cannon’s forgotten Tucker Brook Trail, which was cut on the northwest side of Cannon in the early 1930s but was abandoned after the tramway was built on the northeast slopes in 1938. The start of the trail was cleverly camouflaged by a row of closely spaced spruce trees. My ski partner Dave and I finally discovered it thanks to some tell-tale tracks that led into an impenetrable thicket. We leaned into the wall of spruce trees and, like ghosts walking through walls, burst through to another world: just beyond the trees lay a beautiful 10-foot-wide swathe with a foot of powder. We swooped down, our skis snapping back and forth through the trail’s signature 13 Turns that start the run.

Tucker Brook, like all CCC trails, has a distinctive personality. The run leaps down the mountain like a joyful but unruly child. The trail has a quirky sense of humor, flipping to the right just as I recover my balance from a challenging set of turns, then rolling into a gravity-defying hard left turn that falls away to the right.

I have been on a mission to ferret out these historic down-mountain trails since the 1980s, when I began researching and writing Classic Backcountry Skiing, the first guidebook to backcountry skiing in the Northeast. As I went in search of new trails to ski, I discovered the old trails—and found that these forgotten runs were remarkable powder preserves and fabulous to ski. These trails were also a window into a short-lived era in the 1930s when backcountry ski trails brought people together in vibrant communities.

Over the last few winters, I have been criss-crossing the region researching a new guidebook, Best Backcountry Skiing in the Northeast, out this winter from AMC Books. I’m happy to report that the old CCC trails shine brighter than ever. But they are joined by a new generation of community-supported ski trails and glade zones that are popping up in mountains throughout the Northeast. I’ll say more about this modern ski movement in future columns.

For now, let me tell you a story. It’s about the quest for the best skiing in the Northeast. It begins in the aftermath of the Great Depression when a ragtag group of CCC men showed up in New England with axes and saws and began cutting their way toward the summits.

How the Depression Launched Skiing

They were the unlikeliest ski pioneers. They didn’t ski, most were impoverished city kids, and many had never seen a mountain before. Yet some of America’s most renowned ski trails and ski areas are the legacy of the young men who formed the Civilian Conservation Corps.

The CCC was born of twin crises. The first was the Great Depression: by the early 1930s, about one-fourth of people under 25 were unemployed. Some two million people were drifting as hobos or vagrants, including 250,000 young people who had been dubbed the “teenage tramps of America.”

The U.S. was also in the grips of an environmental crisis of unprecedented proportions. Where forests had once covered 800 million acres of the country, widespread plundering left only 100 million acres of virgin timber by 1933. Destruction of the forests gave rise to soil erosion: by 1934, precious topsoil covering one sixth of the continent had washed away or been carried off by wind. So massive were the dust storms blowing across the Great Plains that snow in Vermont was tinged brown with dust in the spring of 1934.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt swept into office promising to rescue both of these wasting resources. Within a month of his March 1933 inauguration, FDR signed emergency legislation creating the Civilian Conservation Corps. The CCC was charged with hiring unemployed men to do conservation work. Recruits were drawn primarily from families on the relief rolls, and each man earned $30 per month for his work, of which about $25 went to his dependents.

The CCC was in existence from 1933 to 1942. Some 2.5 million men passed through “Roosevelt’s Forest Army,” making it the largest peacetime government labor force in American history. The “CCC boys” improved millions of acres of forest and park land, built roads, constructed irrigation systems throughout the West, fought forest fires and provided disaster assistance. Their most visible and enduring legacy is the parks they built. In the South, 13 states had no state parks and half had no parks at all in 1933; within six years, the CCC had built parks in 10 of those states. The CCC ultimately developed hundreds of national, state, county and municipal parks around the country.

So how did a federal jobs program end up cutting ski trails? The explanation lies with the fact that the CCC contingents in each state fell under the authority of the state forester. Among the state foresters were a handful of ski enthusiasts. When thousands of able bodied axe-wielding men were put at their disposal, these foresters had just the job for them.

The best known of the skiing foresters was Perry Merrill, state forester of Vermont. Merrill had attended forestry school in Stockholm, Sweden in the Twenties. It was while a student there that he glimpsed the legendary Scandinavian passion for skiing. Merrill left Sweden with a vision: perhaps Americans would pursue skiing with equal zeal if they were provided with the proper trails. Maybe skiing could help uplift the poor, rural state of Vermont, his home.

When Merrill was put in charge of the Vermont contingent of the CCC, he asked Charlie Lord, then an unemployed state highway engineer, to lead a CCC crew in cutting ski trails on Mt. Mansfield, the state’s highest mountain located in Stowe.

“There weren’t too many people who knew much about skiing, and I knew hardly anything, but I did ski,” Lord told me in one of several interviews that we did in the 1990s (he died in 1997 at the age of 95). Lord complied by leading a crew of 25 CCC men in July 1933 and cutting the Bruce Trail two miles up the southeast side of Mt. Mansfield to the Toll Road. The trail was an instant hit. Skiers came from hundreds of miles away to ski the Bruce, and in February 1934 it was the site of the first downhill ski race on Mt. Mansfield. Burlington golf champion Jack Allen won the race in nearly 11 minutes; Lord came in second.

Encouraged by their success, Lord and the Vermont CCC men cut a half-dozen more trails on Mansfield, which formed the nucleus of the Stowe ski resort that began in 1936. In his seven years with the CCC, Lord also consulted on mountain design for numerous other Vermont ski areas, including Mad River Glen, Okemo, Burke Mountain, Killington, Middlebury College SnowBowl and Mount Ascutney. Perry Merrill, who died in 1993, wrote proudly, “The CCC made Vermont the Ski Capital of the East.”

New England was the greatest beneficiary of the CCC’s ski trail blazing. The New Hampshire CCC contingent was one of the most prolific, contributing ski trails on Mts. Washington and Cardigan, and on Cannon, Wildcat, Bald, Piper and Belknap Mountains. The Maine CCC cut ski trails on at least four mountains, and the CCC groups in Massachusetts and Connecticut also blazed trails for skiers.

The CCC cut a smattering of ski trails in the western U.S., but skiing in the west did not take hold in earnest until after World War II. The most notable western ski trails cut by the CCC were the first runs at Sun Valley.

My first taste of Charlie Lord’s talents came when I went skied the Teardrop Trail, which runs down the west side of Mt. Mansfield to Underhill. It was designed by Lord and cut by the CCC in 1937 but was abandoned when the Stowe ski area was built on the east side of the mountain. The Bruce Trail, which runs from behind the Stone Hut (another CCC creation) down to the Stowe Mountain Resort Cross-Country Center, remains a backcountry jewel.

The Teardrop and Bruce offer exactly what Lord and his friends dreamed of when they cut the trails eight decades ago. They both cling closely to the undulating contours of the mountain, turning where the mountain turns. Variety is the hallmark of these trails, and they still hold my interest and challenge me even after scores of descents.

Lord’s magic formula is revealing in its simplicity. “When we put in trails, we just put them where we liked to ski, and where we could ski,” mused the ski trail architect as we sat in his living room 30 years ago, his cat on his lap and Mt. Mansfield beaming outside. “We had to avoid ledges and brooks, and we had to thread the trail down the mountain as near as we could to a good fall line without undue obstacles.” He observed with a grin, “We generally found enough obstacles without putting them in.”

Recently, I stood at Cannon’s ski area boundary sign and peered down the passageway on the other side. It was winter 2020, more than 30 years since I first hunted around and found the Tucker Brook Trail. The obvious entrance made clear that this trail no longer secret. “After you,” offered my partner, Patrick Kane, lifting up the rope.

I slid through, once again feeling the rush of time travel as I entered another world. n

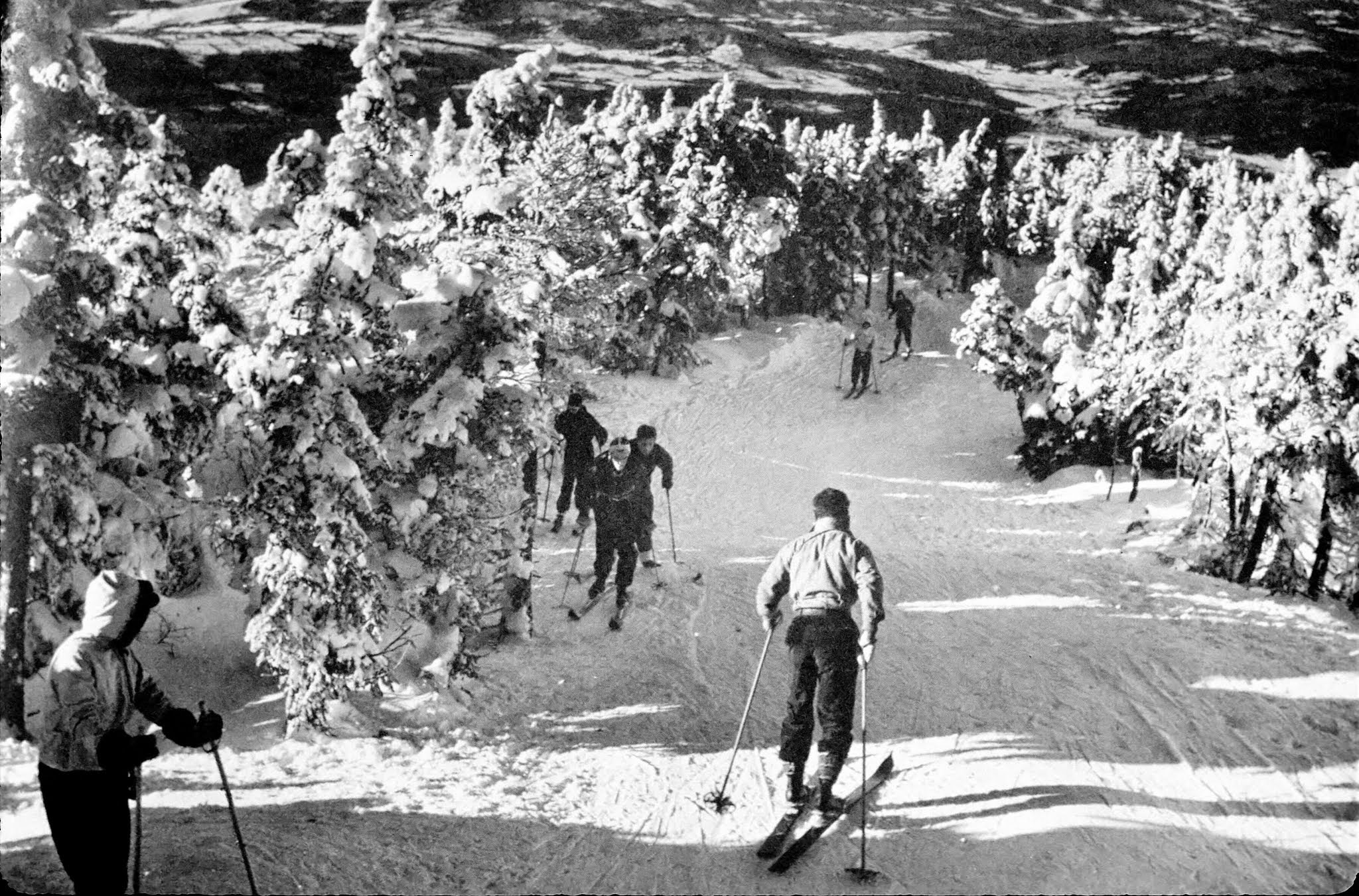

Opening photo: Emily Johnson skis a line down to Stowe’s Ranch Camp that was originally cut in the 1930s by the Civilian Conservation Corps. The CCC men lived at the camp all summer, cutting some of the area’s first trails. Photo by Brian Mohr