Extreme Skier Dan Egan on his Wild Ride

The most recent Warren Miller ski film, Future-Retro, features them: Dan Egan and his brother John, slaying runs in Montana — flashbacks to the wild adventures they have filmed over three decades. Though they’ve skied on every continent, both Egans have made New England a home base: Dan, a New Hampshire resident, was a longtime Killington ambassador and John, a Mad River Valley local, has been a fixture at Sugarbush for four decades. In the new book, 30 Years in a White Haze, Dan Egan and co-author Eric Wilbur tell the story of how Dan and John were some of the pioneers of adventure skiing and the impact it had on Dan’s life. Here is an exclusive first excerpt.

In May of 2000, my brother John and I were in northeastern Canada, on the frozen coast of Ungava Bay on the Arctic Ocean in a blinding windstorm. I had gotten separated from my group and was seeking shelter from the wind against a big piece of ice. John, Dean Decas, and cameraman Eric Scharmer were with the Inuit guides, a hundred or so yards away. And I was shaking from a flashback of being lost in a snowstorm on Mount Elbrus in Russia, ten years earlier.

We were on a three-week trip to make a television documentary on adventure tourism in northern Quebec. Our objective was to traverse east on the Torngat Mountain range from the coast of Ungava Bay to the Labrador Peninsula. Our main goal was to ski Tower Mountain, a stand-alone, pyramid on the border with Labrador.

We were traveling by snowmobile and living with the Inuit, building igloos at night, fishing for Arctic char to complement our meals, ski touring, and climbing the endless mountain chutes along the way. A year earlier, John and I had spoken about a reunion trip back to Mount Elbrus, but decided a new adventure would be a better way to celebrate, rather than going back to the site of such tragic loss. So, I organized this trip, through a grant provided by a partnership with the Canadian and Quebec offices of tourism, to document and discover whether ski touring would be possible in this frozen land.

However, here I was hunkered down in another wild storm—scared, unable to find my way in the Arctic, remembering Elbrus. In 1990, I had found myself on that mountain in Russia, pinned down by a massive snowstorm, digging a snow cave in a fight for my life. It was a storm that ended up claiming the lives of 15 climbers. One was a member of our group. There had not been much press around the Mt. Elbrus disaster unless you saw my video the Extreme Dream released in 1991.

At 18,500 feet, Russia’s Elbrus, a dormant volcano just west of the Black Sea and north of Russia’s border with Georgia, is the highest peak in Europe. An estimated 25 to 30 people die each year attempting to summit the mountain. In fact, Elbrus has a higher annual death toll than Mount Everest. By comparison, there were eleven deaths on Mount Everest in 2019, one of the deadliest years in the mountain’s recorded climbing history. But as recently as 2016, 30 climbers were estimated to have died in attempts on Elbrus in a single year. In 2004, forty-eight perished trying to reach the summit.

John was not trapped in the storm raging on Elbrus as he and cameraman Tom Day had helped guide nine of the 23 people in our expedition back to the base, while I was on the summit attempt. Five members of our expedition were lost in the storm, only four survived. John and I have an exceptional tight bond that has been tested over the years in the mountains. We have trusted each other for decades. Being alone on that Russian peak became a life changing event in so many ways.

It has been difficult for me to speak of the isolation I feel when surrounded by clouds, wind, and snow in the mountains, or in fog on the open ocean while sailing. My body tenses up, my breathing gets short, and I start to think of what will happen if I can’t find the others or a path forward.

As a pro skier, coach, guide, and sailor, I have found myself in these conditions many times over the years. Even today, 30 years after being trapped on Mt. Elbrus, the sensation remains very personal; I haven’t found a way to express the panic that builds in situations like this. Often, being the one in charge, I mask my fear with confidence and a gentle urgency to move myself and my companions toward safety.

Our trip to Ungava Bay was our second trip up north. Two years earlier, we traveled to Baffin Island, the largest island in Canada, to ski the fjords along the Davis Straight. We stayed on Broughton Island in a small research hut and traveled by snowmobile across the frozen sea to the coast of Baffin to tour, climb, and ski. I liked the North. It’s a world wrapped in snow and ice that brings you back in time.

Since the mid-1980s, John and I built a reputation for skiing the world’s remote locations. We traveled throughout the Eastern Bloc at the end of the Cold War, skied with Kurds in Turkey during Desert Storm, pioneered heliskiing in Chile, skied the Martial Glacier above the Drake Passage on the southern tip of Argentina, snuck into Lebanon to ski in the mid-1990s, and skied the classic lines across Europe and North America.

Together, John and I have chalked up more than 50 first descents, launched off cliffs the height of 12-story buildings, and skied more than our share of pristinely perfect powder snow on mountain peaks around the globe. Our mountain antics were documented by filmmakers and writers, and shared on VHS tapes, TV shows, magazines and books years before the advent of the X-Games, terrain parks, GoPro, YouTube, or social media.

The brother angle played well. John, six years my elder, was my childhood hero. His bold personality and life-on-the-edge attitude left me searching for a way to gain his attention and confidence. And I found it in the marketing of our brand as “The Egan Brothers” through films, television shows, merchandise, and sponsorships which I managed and produced.

Raising a large family, my parents Marlen and Robert embedded a work ethic and goal-setting standard that lives deep within me and all six of my siblings. Mary Ellen, Bob, John, Sue, Ned, and Mike are each fiercely independent souls with big hearts and a belief system of service to others. I love them all. They have all supported me in the good times and in the hard times, but most of all they have accepted my rough edges and all that comes along with them. There is nothing like family for creating tension, releasing emotion, and caring. I’ve never found a replacement for it—and trust me I have looked.

Skiing is timeless and simple, which is why I love it—the satisfaction and joy of gliding on, over, and through snow. This all started for me as a young boy. Every fall, just after Halloween, we’d trek to the attic as a family and haul down all the boots and clothing, bring the skis up from the basement, and turn our living room into a ski shop. Boots were tried on, bindings adjusted, and poles handed out. Whatever fit automatically became yours. Then we’d begin waxing our skis in the basement, place our gear by the cellar door, and wait for snow.

We lived on a hill, so when snow fell we’d ski and ride the yellow Snurfer sled down the hill, over the jumps, then run back to the top for another run. On Saturdays we’d load up the car, head toward the Howard Johnson’s parking lot at the exit to the highway, and board the Blizzard Ski Club bus for New Hampshire. I took ski lessons until I was sixteen. We were taught by the Austrians at the Paul and Paula Volar Ski School at Mount Sunapee and Cannon Mountain, as well as at the Egon Zimmerman Ski School at Blue Hills, just a few miles from my family’s home in Milton, Massachusetts.

In the 1970s, Bob and John always had cool gear. I remember when they got their Olin Ballet skis—plus Jet Stix, an extension for the back of the boots that would allow you to lean back and do freestyle tricks. My sister Mary Ellen was an expert skier as well, and would challenge us younger kids to turning contests—she was the queen of quick turns, feet locked together, smooth and flawless. In high school, when I finally got new skis and boots that fit, my world opened up. The skills I’d learned from ski school expanded to skiing the woods, moguls, and racing down icy runs.

Skiing fostered two main things for me: independence and confidence. The independence was forced on me by my two older brothers refusing to wait for a ten-year-old kid. The confidence grew over time, knowing one day I would catch ‘em. Once I was a senior in high school, having been tested by Bob and his friends on the Norwich University Ski Patrol (where he went to school) and at Sugarbush Resort (where John was a ski bum), I finally had my first taste of the wild side of life and what real skiing felt like off the beaten path. My skills were coming up to their standards.

I jumped my first real cliff at Mad River Glen Ski Area in Vermont. In the early 1980s, the landings were flat. I was skiing with one of John’s ski bum friends, Tim Ritson. It was a fresh powder day and he was showing me all the cliff drops in the woods. He was telling me, out West you can do this and ski away from the cliffs—it was steeper and deeper. Since that day, I’ve been hooked on the thrill of heading toward the edge of a cliff and flying off it.

I’ve come to call it “the eternal now,” when everything slows down and then bang! you land in a pillow of snow. That day with Tim, I got a taste of that feeling and wanted more. That pursuit almost led John and I to our death in March of 1990 while filming for Warren Miller in Grand Targhee when a truck-size cornice let go on the edge of a ridge. Below, a five hundred foot cliff. John actually made a turn in midair that saved his life. It’s a scene many remember from the movie Extreme Winter and it went on to be the most viewed Warren Miller film clip of all time.

Meeting, skiing and working with Warren Miller was fuel for my life. His films provided me with a platform, a way to belong to the industry I could never have foreseen. He introduced me to the art of filmmaking, storytelling, and how to distribute the end product. The door he opened became a path to many possibilities for my ideas, passion, and drive. He once told me: when I skied, I should think about the beauty of the place and my role in it—which was to complement the surroundings, to be the exclamation point on the mountain. His many examples have been inspiration for this book, my films, articles, and career.

The experience in Ungava Bay is a typical reoccurring experience I have when clouds gather and gale force winds blow. That May in 2000 I did what I always do: feel the emotions that rush in, breath deep and refocus on the reality of my current conditions. Then I dismiss it with full body shake and let the past escape out my fingers and toes.

I’ve come to believe trauma doesn’t shape your life, rather, it dictates it. Being lost in a storm with winds blowing over a 100 miles per hour, trudging through five-foot-plus deep snow, and digging a snow cave in the battle to survive on one of the precipitous Seven Summits of the world while being separated from my brother, all formed internal reactions I couldn’t control for years afterward.

Walking off Mt. Elbrus alive on May 3, 1990, was the beginning of my adult life as I know it today. I was 26 years old. For the next 30 years, I’ve had to learn to restructure the patterns caused by that traumatic experience. That trip has touched every aspect of my life: relationships with my siblings, especially John; the ending of my marriage in 2001; post-divorce relationships; business and financial decisions, especially when I’ve felt threatened; and where and why I ski the locations I do today.

That trip brought me closer to God and helped me understand the deep and rich roots of faith that run through the generations of my family. It also created my wonderful, rewarding, sober life, which is a constant cycle of discovering who I am.

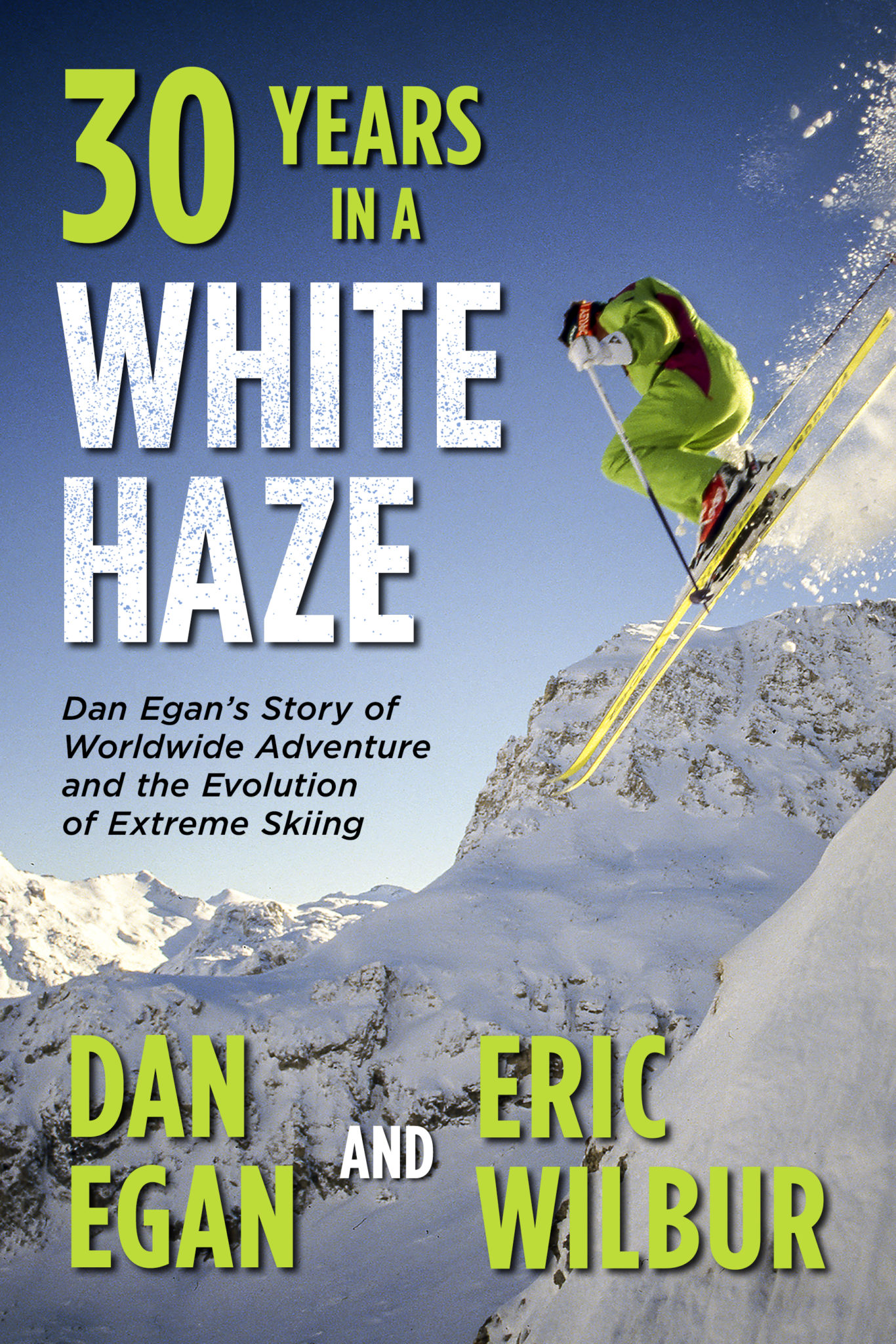

{Opening photo:Dan Egan bites into Apple Core on Lone Peak in Big Sky, Montana while shooting Warren Miller’s 2020 film Future-Retro.]

Pingback: Who Can Ski Vermont? – VT SKI + RIDE