In the Race to Buy Ski Areas, Who Wins?

In the past 36 months we’ve seen the biggest ski resort buying spree in history. What does this mean for Vermont’s 20 resorts? And what does it mean for you?

“When I started Bolton Valley, each ski area in the state was owned by one or two people,” reflected Ralph DesLauriers in early August as he sat in his office at Bolton Valley Resort. “I think most of them were owned by friends who got together to own a ski area, or families. Every area was owned by a real person, and we all kind of helped each other out,” said DesLauriers. “When I left Bolton in 1997, I think I was the last person in the country running the ski area they started.”

DesLauriers started Bolton Valley in 1966 on land his father Roland purchased for lumber. “When I graduated from Burlington High School

in 1953, I knew maybe 12 kids at most who skied. It was something that was for wealthy out-of-state kids. So, I decided I wanted to teach every Vermont kid I could how to ski,” said DesLauriers.

In the first year they were open, Bolton Valley offered every Vermont student one lift ticket per week and one lesson, all for $10 a season. At its peak, Bolton Valley was teaching 2,000 Vermont kids from 40 schools to ski or ride each year in its after school program. I was one of them. Today, that number hovers at around 1,500 annually.

The mountain became a playground for the DesLauriers’ kids as well. His oldest sons, Rob and Eric, were early pioneers in extreme skiing. Rob DesLauriers has been featured in more than 20 ski films. He was one of the first Americans to ski Mt. Everest and, along with his brothers Adam and Eric, he founded a ski film company, Straight Up Films, to document other big mountain ski descents.

When DesLauriers sold the resort in 1997, his youngest son, Evan, was just nine. Twenty years later, Evan, now 30, Adam, 45, and sister Lindsay, 39, told their dad they wanted back in.

In April 2017, after a successful decade in real estate, Ralph DesLauriers bought Bolton back.

That February, Vail Resorts had announced it would buy Stowe for $41 million. In July 2017, a conglomerate formed by Henry Crown & Company of Chicago and Denver-based KSL Capital Partners bought Intrawest Resort Holdings and formed Alterra Mountain Company in January 2018. That started the biggest consolidation spree the American ski industry has ever seen. In June 2018, Vail Resorts announced plans to purchase Triple Peaks, LLC, a group of three resorts that had been managed by Tim and Diane Mueller, former owners of Okemo, Vt., Mt. Sunapee, N.H. and Crested Butte, Colo. As of that deal’s closing on October 4, Vail Resorts owned 18 ski resorts. On February 21, 2019, the company announced plans to purchase Falls Creek Alpine Resort and Hotham Alpine Resort, two ski areas in Victoria, Australia. Once that deal closes, which is expected to happen in June 2019, the company will own 20 ski areas.

Not to be outdone, Alterra, after a lightning buying spree, now owns 14 ski areas, including Stratton, Mont Tremblant, Squaw Valley and Mammoth Mountain.

Note: On Nov. 13, 2019, Sugarbush Resort announced that it had entered into a purchasing agreement with Alterra Mountain Company. The deal is expected to close in January 2020 and when it does, Alterra Mountain Company will own 15 North American ski areas.

Peak Resorts, parent of Mount Snow, owns 17 resorts (mostly smaller urban markets) and POWDR owns Killington and Pico in Vermont along with another six ski areas out west.

Note: On July 22, 2019, after this story was originally published, Vail Resorts announced it had entered into a definitive merger agreement with Peak Resorts to acquire 100 percent of the company’s outstanding stock. When the deal closes in fall 2019, it will be an approximately $264 million transaction that leaves Vail Resorts as the only publicly traded ski company in North America.

Starting in 2019-2020, the Epic Pass ($939) and Epic Locals Pass ($699) along with the Military Epic Pass ($129) will offer skiing at the 17 ski areas previously held by Peak Resorts, Inc., among them Vermont’s Mount Snow and New Hampshire’s Attitash, Wildcat and Crotched mountains.

But it didn’t get there overnight.

What followed those initial acquisitions put smiles on the faces of many skiers and riders: the price wars began on season pass rates.

Vail Resorts cut the cost of a Stowe season’s pass in half, from a high of $1,860 for the 2016-2017 ski season, to $859 for an Epic Pass (good to varying degrees at 65 resorts) for the 2017-18 ski season. Suddenly, with an Epic Pass, you could ski at Stowe and 44 other destinations for less than a 2016-17 early-bird season’s pass had been any of five of Vermont’s largest resorts. At the same time, day tickets soared in cost from $99 to $131 at Stowe, making buying a season pass all the more attractive.

In reaction, eight Vermont resorts also dropped their pass prices. Then, in January 2018, Alterra introduced the Ikon Pass, which, at $1,099, is now good at 41 resorts.

So, beyond a passion for skiing, why would DesLauriers or any smart business person purchase a ski resort, particularly as winters are getting warmer and snowfall more variable?

The Big Business of Skiing

At the tip top of the food chain, most of the ski resort companies, big and small, are owned by people who, like DesLauriers, have an intense passion for skiing.

John Cumming is a former mountain guide who co-founded Mountain Hardwear in 1993 before founding POWDR. By his own estimate, he’s climbed Mount Rainier 69 times. His wife, Kristi Terzian, was an Olympic slalom racer in the 1990s and no doubt helped influence the World Cup coming to POWDR’s Killington resort.

KSL Capital Partners, the private equity giant fueling Alterra Mountain Company, is led by, among others, Eric Resnick and Michael Shannon, both former executives at Vail Associates (the private predecessor to Vail Resorts, Inc.). Rusty Gregory, CEO of Alterra, started his career as a liftie at Mammoth Mountain and is a former heli-ski guide. Rob Katz came from Wall Street but has been involved with Vail Resorts since 1991, when he worked as a senior partner at Apollo Management, L.P., an affiliate of the former majority shareholder in Vail Resorts. He has served as Vail Resorts’ CEO since 2006.

These men are skiers, but they are also business people who recognize that beyond the savings that owning multiple resorts can offer, multiresort pass sales bring access to the names, data and credit cards of hundreds of thousands of people who can afford to spend close to $1,000 a year on a season pass, plus more on travel, lodging, dining and the other amenities connected with the sport.

For Alterra, this means it can cross-market its CMH Heli-skiing operations to Stratton skiers. In the same way, Vail Resorts can market rooms at its Rock Resort luxury hotels in Colorado and Wyoming to Okemo and Stowe skiers. POWDR can market its Woodward action sports centers and programs to Killington and Pico skiers and riders. Large companies can also consolidate the purchasing of items ranging from toilet paper to coffee (Vail Resorts will be now be serving Starbucks at Stowe and presumably Okemo) to Pisten Bullys.

Consolidation is also a hedge against bad weather and brings in revenue during a part of the year when many resorts have little or no cash flow. In 2017, Vail Resorts CEO Rob Katz told CNBC’s Squawkbox: “The benefit of [the Epic] pass was that… we’re selling all these passes before the season starts, so we take all the risk of weather, of economic fluctuations, out of the season before we even start it.”

These strategies allow the companies to make big capital investments. In March, just three months after Alterra Mountain Company acquired Stratton Mountain, the company announced plans to invest $10 million in capital improvements at Stratton for the 2018-2019 season. Similarly, in June, Vail Resorts announced plans to acquire Okemo Mountain Resort and to invest $35 million in capital improvements to be shared across Okemo, Mount Sunapee and Crested Butte over the next two years.

And then there’s the element of scarcity: there is limited land that ski areas can operate on and increasing restrictions on ski area development. The last major ski areas to be built in North America were built in the 1980s at Beaver Creek, Colo. and Deer Valley, Utah. Bolton Valley was the last major ski area to be built in the Northeast.

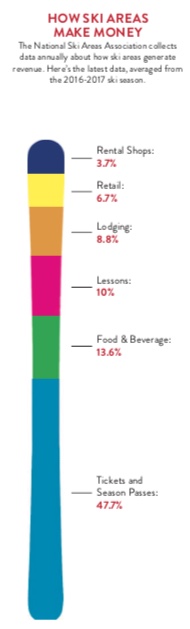

How Ski Areas Make Money

In the ‘80s and ‘90s, resort owners were looking to make money in real estate and began building everything from ski shops to spas at ski areas. Ralph DesLauriers financed Bolton’s operations by building condo complexes. Les Otten, the legendary founder of American Skiing Company, financed the only acquisition spree historically comparable to those of Vail Resorts and Alterra by building hotels and condos at Maine’s Sunday River and Sugarloaf and Vermont’s Killington and Mount Snow. At its height in the late ‘90s, ASC owned nine resorts, including Killington and Sunday River.

American Skiing Company, as New Englanders well know, eventually failed and collapsed in 2007.

And for the most part, the pattern of resorts investing in real estate has changed.

In 2015, Katz told The Vail Daily that Vail Resorts was no longer interested in developing real estate at its properties. “We’d rather spend our money on the mountains,” he said, citing past conflicts with resort communities as a contributing factor to the decision and saying the company will court third party developers going forward. When Vail bought Stowe, all of the Spruce Peak complex’s lodging remained with previous owner AIG and independent homeowners.

In Vermont, the outlier to this trend is Jay Peak, which is currently under receivership and up for sale, along with its recently constructed water park, Clips & Reels Recreational Center, its ice rink and more than 3,000 beds.

“Jay Peak is unique because of the way our balance sheet is constructed,” says general manager Steve Wright. “We are not as focused on lift ticket sales and rely as much on lodging and real estate. We’ve done that consciously to protect ourselves from the vagaries of weather.”

POWDR takes yet another approach. In addition to its nine mountain resorts, which boast 3.5 million skier visits annually, it owns Outside TV, Woodward and Human Movement adventure and athletic training camp brands and Sun Country Tours, a whitewater rafting guide service. In the past few years, its focus on the outdoor adventure lifestyle has been reflected in Killington’s buildout of the mountain bike park (now the largest in the East), and this summer’s addition of the WreckTangle. Killington has also been hosting events such as the Fox US Open of Mountain Biking, the Spartan Race and Under Armour Mountain Running series, as well as the Audi FIS Ski World Cup.

“Community experience and purity of place are why we do POWDR,” says chairman and founder John Cumming. “We’ve been successful over the last 25 years because we’ve been really, really patient,” says Cumming. He runs POWDR with a mountaineer’s sensibility for risk: growth (which he likens to summiting) is optional, but sustaining the company’s current offerings without allowing them to suffer in quality is mandatory. “We recognize that up is optional and down is mandatory, a climbing analogy I’ve used many times to think about growth,” said Cumming. Instead of acquiring new resorts, POWDR has been investing heavily in growing skiing and other activities at its existing ones. In September 2018, POWDR announced plans to invest $25 million in on-the-hill upgrades at Killington for the 2018-2019 season.

Peak Resorts has also been investing. Over the last few years, the company put $52 million into Mount Snow, Vt. bringing snowmaking to 80 percent of its terrain and, this year, adding the new Carinthia base lodge. The company also bought one of New York’s largest resorts, Hunter Mountain, in 2015, and has committed $9 million toward a 25-percent expansion of the mountain’s terrain. On September 14, 2018, the company announced it had entered into a definitive agreement to acquire privately-held Snow Time, Inc. (“Snow Time”) for $76 million in total consideration, adding three more Pennsylvania resorts to its fold.

Peak Resorts started its ski resort life in 1981 when Tim Boyd bought a struggling nine-hole golf course outside of St. Louis called Hidden Valley and converted it into a ski area. Today, the Missouri-based company owns Mount Snow and 17 other resorts across the Midwest and East Coast. It is one of two publicly-traded ski resort companies, (the other is Vail Resorts). Peak Resorts was also one of the first companies to actively pursue what are commonly referred to as “feeder” resorts in the industry.

According to Jesse Boyd, Vice President of Operations for Peak and Tim’s son, the majority of the company’s 17 properties are located within a one hundred-mile radius of New York, Boston, Philadelphia, Cleveland or St. Louis. “We got started in the business running small metropolitan ski areas and transitioned to running medium and large resorts [such as Mount Snow, Attitash and Wildcat Mountains] and use those small metro area resorts as a feeder system,” Boyd said.

That’s a strategy Vail Resorts has since pursued with its 2012 acquisition of Afton Alps, just outside of Minneapolis, Mount Brighton near Detroit and Wilmot, between Chicago and Milwaukee. As Katz told Men’s Journal in March 2017, “[Now] We get access to 800,000 skiers in Chicago and 400,000 each in Detroit and Minneapolis.” As of press time, word had it Vail Resorts was also eyeing Japan’s Hakuba Valley resorts as well—the resorts ended up being added to the 2018-2019 Epic Pass through what Vail Resorts called “a long-term alliance.”

Boyd says the regional focus of Peak Resorts’ acquisitions has positioned it well to compete with Vail Resorts and Alterra. The company’s motto is “We don’t meet expectations, we set them.” Boyd says Peak Resorts caters to weekend and local skiers, not the destination crowd that Vail courts. “Our pre-season pass sales are up 14 percent over last year, and our Drifter pass [$399] for 18 to 29-year-olds was up 47 percent,” Boyd reports. He said revenue on pass sales overall was up 16 percent in 2017-2018. “The consolidation stuff hasn’t had a lot of effect on us.”

Note: Vail Resorts’ acquisition of Peak Resorts closed in late September 2019.

The Indie Response

Win Smith, the owner and president of Sugarbush Resort skis over 100 days a year and is on the mountain at 9 a.m. almost every morning. The son of a founder of Merrill Lynch, he had a 28-year career in finance before he purchased Sugarbush in 2001.

Since owning Sugarbush, he’s overseen more than $65 million in resort improvements and $50 million in onsite real estate development.

He also anticipated Vail’s move into Vermont. On March 15, 2017, just three weeks after Stowe’s acquisition was announced, Sugarbush cut its adult season pass price by 30 percent, undercutting the Epic Pass that year by $60. In the same move, it offered even cheaper passes for 20-somethings, 30-somethings, seniors and baby boomers, and remained on the Mountain Collective Pass, a $449 pass option that offers two days of skiing at 17 resorts across North America.

How did that work out? Smith says well. “Our ability to quickly anticipate the Epic Pass paid off. We grew our base that year.”

According to Smith, “as long as it’s cash-flow positive, a private company can make long-term decisions that public companies have a harder time doing.” The result? “We can be more nimble in our pass offerings.”

Smith says that so far, Sugarbush isn’t feeling any negative effects from the Epic Pass’s presence in Vermont. Nonetheless, he decided to join Killington and team up with Alterra Mountain Company for the 2018-2019 season by offering seven days of skiing at Sugarbush to Alterra’s Ikon Passholders.

As of press time, Sugarbush didn’t get any revenue from Ikon Pass sales, but Smith said that’s OK because it draws new interest in the resort. Sugarbush has also seen an increase in skier visits since it joined the Mountain Collective in 2017. Most of those were from first time skiers or skiers new to Sugarbush.

“The value of joining the Ikon Pass for Sugarbush is exposure,” said Smith. Sugarbush, which brands itself around “community,” also has a strong local following, with more of its season pass sales coming from Vermont than from any other state, including Massachusetts and New York.

Note: On Nov. 13, 2019, Alterra Mountain Company announced it had entered into an agreement to acquire Sugarbush Resort. For more on why, from Smith, head here.

Just next door, Mad River Glen, which is operated as a cooperative, was one of only a few Vermont ski areas not to lower its season pass prices in response to the Epic Pass’s release in 2017. According to marketing director Eric Friedman, for 2016-2017, roughly 55 percent of Mad River Glen’s revenue came from day lift tickets. Additionally, Friedman reports that about a quarter of Mad River Glen’s skiers are first-time visitors to the area. The co-op also has shareholders who commit year after year to season passes.

“We don’t have real estate or big hotels. We make money from selling lift tickets and that’s why so many small ski areas are profitable,” says Friedman. “Once you’ve covered the basic costs of operations at a ski resort, the more lift tickets you sell, the better you do.”

Building a Niche

Bill Jensen, the former CEO of Intrawest who currently runs Telluride Ski Resort, isn’t so hopeful for Vermont’s independents.

“I think [the consolidations] will change this market share game that’s been played in New England for the last 40 years,” he said. Jensen pointed to New England’s fairly stagnant skier visits, which, according to data compiled by the National Ski Areas Association, have fluctuated between roughly 9 million and 14 million annually since 1978, while Colorado’s have grown steadily from 15 million to 21 million over the same period of time. According to the Vermont Ski Areas Association, skier visits to Vermont’s 20 resorts have averaged between 3.9 and 4.6  million annually over the last ten years.

million annually over the last ten years.

“I can’t predict who will be the winner in New England; Alterra Mountain Company or Vail Resorts,” Jensen said. “However, I think that for maybe 25 percent of the remaining resorts, it’s a possibility they can be successful if they really market their niche.”

Jensen says American skiing is about selling an experience, and the key to success as an independent resort is in knowing what unique experience you’re selling.

And that, says Vermont Ski Areas Association President Molly Mahar, is exactly what Vermont is good at. “We have a mystique here in Vermont,” says Mahar.

Vermont’s 11 independent ski area operators and owners reflect the state’s character and the mountains they represent. They have an entrepreneurial spirit. They are pragmatic and each can tell you exactly what sets their skier experience apart.

They are also keenly aware of who their competitors are within the statewide market.

According to a 2015 report by the University of Vermont’s Vermont Tourism Research Center, 23 percent of overnight visitors to Vermont overall are from Boston and 20 percent are from New York. Since 2002, Canadians have accounted for as many annual visits as Boston residents.

According to Geoff Hatheway, president and part-owner of Magic Mountain, every regional demographic is different, as are its sub-groups: Boston has a reputation for having a high density of athletic and advanced skiers focused on challenging terrain. According to Sugarbush’s Smith, the New York market likes good terrain, but they also like amenities. Bill Stritzler, owner and managing director of Smugglers’ Notch, notes that the Quebecois visit Vermont ski areas year-round.

Hatheway was one of a group of skiers who purchased Magic in 2016. The previous season it had been closed for much of the year. Hatheway recognized that, like Mad River Glen, what Magic could offer was no-frills, throwback skiing with a healthy dose of community. And it’s become just that: a serious skier’s mountain where the lines are steep, the beer is cheap and the lift tickets sometimes sell out.

With its iconic, red chairlift and gladed tree skiing, Magic is a throwback. “We are a back to the future kind of a place,” Hatheway says. Day lift ticket sales are a bigger source of revenue for them than season passes. And yes, if it gets too busy on a Saturday powder day, they will stop selling day tickets to keep lift lines and crowds down.

Hatheway said that while he is confident in the viability of Magic Mountain’s market niche, he’s afraid for independent ski areas in Vermont. “For the major players to be interested in mountains in Vermont is good,” he says. “But quite frankly, it’s a very difficult market for independents. The multi-pass environment is difficult to navigate.”

Hatheway suggested that local operators have a different sense of investment in their businesses than corporations. “It keeps you up at night. You don’t want to see these places not be open, to have people not have this as a part of their lives. I feel that personally, that overriding sense of responsibility for this place and what it represents for these people,” says Hatheway. “I want this place to be here for my kids, for our kids.”

AUTHENTIC VERMONT

The word “authenticity” came up again and again in interviews with owners and operators. By way of explanation, Ralph DesLauriers told the story of his first business: a farm to table restaurant he opened in his parents’ farmhouse in South Burlington. Instead of doing what the other Burlington restaurants were doing, which was fine dining, he decided to

do what he knew and keep it rustic. It was a hit. The same parable has guided his development of Bolton Valley. As he put it, “You can’t out-New York a New Yorker, but you can out-Vermont ‘em.”

One of the oldest and most notoriously “Vemont-y” of ski areas, Mad River Glen has a similar approach. When it came time to replace its iconic single chair in 2007, the shareholders decided that rather than upgrade to a double or a quad, they would put in a new single to preserve the original character. Mad River Glen skiers and Mad River Valley community members raised the $1.8 million to do it. This year, Mad River Glen celebrates its 70th year, in part because it knows its niche.

According to Friedman, that niche is steep, gladed terrain covered in natural snow and no frills. “We might not have gold-plated toilets, but our experience is really unique,” says Friedman. “You could ski at any other ski area all day long and at the end of the day, you’re not tired. But if you ski a full day at Mad River? You feel it.”

Bill Stritzler has worked at Smugglers’ Notch in a leadership role since 1987 and owned the resort since 1996. He stands by the idea that you can’t beat a conglomerate at what it does. As he tells it, his strategy at Smuggs’ is to find out what the industry giants are doing and do the opposite. “We have an internal philosophy which says we are not going

to pursue anything that we don’t believe we can achieve the level of best at,” says Stritzler.

That philosophy has led to Smuggs’ being “single-mindedly focused” on kids and families for the past 25 to 30 years, because being the best in that category felt attainable. In 2017, Smugglers’ Notch was rated number one for its programming for children and families in a survey of readers of Ski Magazine and named the top resort in the East and eastern Canada. A season’s pass at Smugglers’ Notch, at about $600, has always been cheaper than the Epic Pass. “Our season pass sales were up last year and, so far, our preseason sales are on target,” says Stritzler.

The same tenet guided the resort’s relationship with real estate. In the 1970s, Smugglers’ Notch began investing in timeshare condo development because share ownership was more financially attainable for families and eliminated the hassle associated with owning a property. “We kept it small, internal, and we never got out. Today we have 6,000 owners and have a sales and marketing contract with Wyndham.”

Stritzler also adds: “When the industry was putting in high-speed lifts, we didn’t think we could compete in spending capital dollars, so we decided to invest heavily in summer [25 years ago] when the rest of the industry was not.” Today, Stritzler says Smuggs’ is as busy during the summer as in the winter thanks to family-oriented facilities like the FunZone 2.0, two world-championship disc golf courses, mini golf, a water park, mountain biking trails and kids’ summer camps.

Who Wins?

According to Kelly Pawlak, President and CEO of the National Ski Areas Association, the real winners in all of this heightened competition are the skiers and riders. “This is not the first time we’ve seen consolidation, it’s just a little larger scale than in the ’90s,” says Pawlak, and it’s working to bring in more season pass customers.

Pawlak reports that even small and mid-sized resorts are seeing an increase in the skier visits they see from season passholders. “It’s important to remember when we talk about consolidation, that the rising tide does seem to float all boats.”

Pawlak says the sale of multi-resort passes generates stability across the industry by ensuring that operators have the capital they need to function through the ski season before it starts. It also reduces their dependency on natural snowfall, which Pawlak says is the biggest driving factor in why people ski where they ski. It’s also a benefit for skiers, who, in a drought year, can chase snow.

However, as Steve Wright, general manager of Jay Peak points out, “The consolidation and rise of the multi-resort season pass has made skiing cheaper for the avid skier, but with day ticket prices soaring it has not benefited the newcomer so much.” He’s hoping Jay Peak can capitalize on that segment of the market that is no longer being served as many options.

“We’re as much about the new skier, or the some-time skier who may come for the water park and ski one day or play hockey or ice skate. We’ve intentionally kept our lift tickets low,” says Wright, noting that a

day ticket will go for $89 this fall. That’s a sharp contrast to the three-figure prices at many ticket windows around the state.

“There is still room in the market for smaller ski areas that focus on introducing kids and families to skiing [and riding] and ski racing,” said Vermont Ski Association President Molly Mahar. “Those sorts of operations are not necessarily competing with a Killington or a Stratton.”

That’s what keeps Boston’s Hunt Stookey and his family driving up to ski at Sugarbush each weekend. He grew up coming to Vermont to ski and now his two kids are part of the Green Mountain Valley School ski club.

“Sugarbush feels like authentic Vermont,“ says Stookey. “I love that the lodge at the base of Mt. Ellen is 50 years old and I still bump my head on the stairs going up and down. It’s part of the history of the place,” he says, adding that the eclectic culture of the Mad River Valley is part of Sugarbush’s allure, too.

Stookey adds: “On the snow there’s a real local vibe and most people you meet are serious skiers, passholders who are there for the gnarly terrain and narrow trails. It’s old-school and it reminds me of what Vermont skiing was when I was a kid.”

Peter van Raalte, a lifelong Stowe skier and second homeowner, was grateful for the price cut to season passes but worries it will cause overcrowding at the resort. “It’s just the way of the world that nothing ever stays the same, but Vail Resorts is… the McDonald’s of skiing in some respects. They’re all about numbers,” says van Raalte, who works in finance in Manhattan. However, he says, “Vail can’t change the mountain or that killer view from the top. It’s the trails, the lake effect snow from Lake Champlain and the terrain that make Stowe the best in the East.”

“It’s bittersweet,” says Jack Holby, a lifelong Okemo skier who worked eight seasons at the mountain starting in high school, about Vail’s acquisition of his home mountain. “It marks the end of a family-owned mountain which in part represents the rugged, raw individualism that skiing embodies. While the investment may be nice, I’m also worried that it’ll make the mountain too corporate and too ritzy.”

Back at Bolton Valley, Ralph DesLauriers says he’s not worried about a future in which two entities dominate season pass pricing. “I think they’re buying other ski areas because they don’t think that there will be any more of them built,” he says. “Big companies always want to get bigger, and my guess is that they figure that if they can control the market, they can control the prices at will.”

As for ticket costs? “I want them to raise those prices,” says DesLauriers.

I asked DesLauriers why he ever sold Bolton Valley. He said, with a sigh, “I was running out of gas and I really couldn’t afford to keep the place going.” And he didn’t want to see it die.

“If there’s one thing we did here at Bolton Valley that I am most proud of, it’s teaching all of those Vermont kids how to ski,” he said. He estimates that in 58 years, Bolton Valley has taught upwards of 27,000 Vermont school kids to ski. He hopes some of them will bring their kids there.

“For a lot of Vermont families, that $115 lift ticket is out of reach,” says DesLauriers. “That’s why we offer night skiing for $25. Vermont families ski more than anybody. Rain or snow, it’s the locals who will always turn out and carry you through.”

Photo Caption: For powder hounds, the rise of the multi-resort pass means you can chase a snowstorm from Squaw Valley, Calif. to Sugarbush, Vt., or Silverton, Colo. to Mad River Glen, all on one pass. Here, Eamon Duane skis Mad River Glen, Vt. (aka “Vtah”). Photo by Brian Mohr of Ember Photography

Last updated November 13, 2019.

Nice article, thanks!